Blog Archive

Waking Up at 97 Orchard Street

Spring is just around the corner… we hope! To help us through these last winter days, we turn to hot tea and coffee for warmth and caffeine. Here at the Tenement Museum, we also imagine how they might have awakened the senses of residents at 97 Orchard Street.

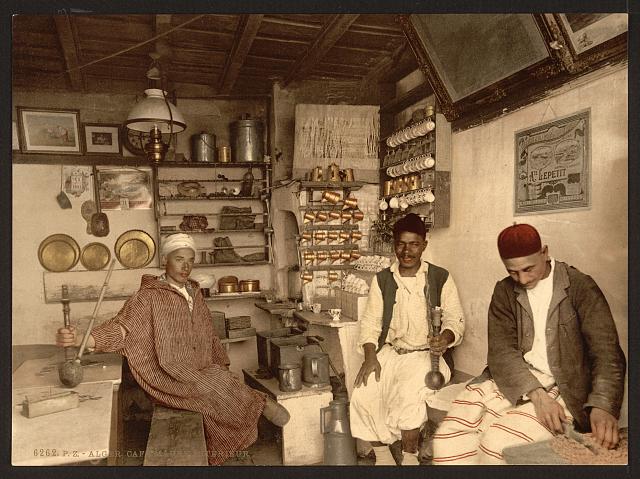

Evidence of coffee and its preparation can be found throughout our tenement. In the Baldizzi apartment there’s a canister of Maxwell House Coffee. In the Confino apartment, visitors take a whiff of Turkish coffee. And a coffee grinder is now a hands-on object in the “Meet Bridget” program. How did these beverages get to New York in the first place, and how would the families in our tenement at 97 Orchard Street have consumed them?

Though coffee had been drunk for centuries in Africa and the Middle East, it did not appear in Europe until the seventeenth century. The Cafe Procope in Paris, which opened in 1689, served philosophers Rousseau and Voltaire (who supposedly consumed 40 cups of coffee each day!) as well as the future emperor of France, young Napoleon Bonaparte.

In early nineteenth-century Germany, women got together to gossip in coffee shops. Uneasy husbands derisively termed these get-togethers “Kaffeeklatsches” (literally, “coffee-gossip”) but for the women involved they served as important opportunities to think and speak freely.

Here in America, early colonists were not big coffee drinkers, but their habits changed following the various blockades on tea prior to the Revolutionary War and War of 1812. By 1810, coffee was available on menus throughout New York City. During the Civil War, coffee was part of the Union Army’s ration, but when the Southern ports were blockaded, the price soared. The price per pound of coffee in 1861 was $3; but by 1864, it was going for $12 to $60 per pound! The preparation of coffee also changed with new technologies in the home; 1860s-era coffee recipes were written for both the hearth and the new iron stove. By the end of the nineteenth-century, the United States was consuming thirteen pounds per capita and importing over forty percent of the world’s coffee.

German, Austro-Hungarian, Ottoman, and Italian families all brought coffee-drinking culture to New York, and you can imagine the aroma of coffee wafting out of the Gumpertz, Schneider, Confino, and Baldizzi apartments in the mornings, whether it was 1872 or 1935.

During the era of the Jewish East Side, Houston Street, at the center of the Hungarian and Romanian communities, was known as café row. Coffee was often served “shwartzen,” a small pot of cream and a tumbler of water. Or, coffee with milk would have been served in a glass. Josephine Baldizzi, whose family lived in 97 Orchard Street during the Great Depression, remembers that her parents had bread dipped in coffee for breakfast and that her mother would save the used coffee grounds to make several more batches of coffee in order to save money.

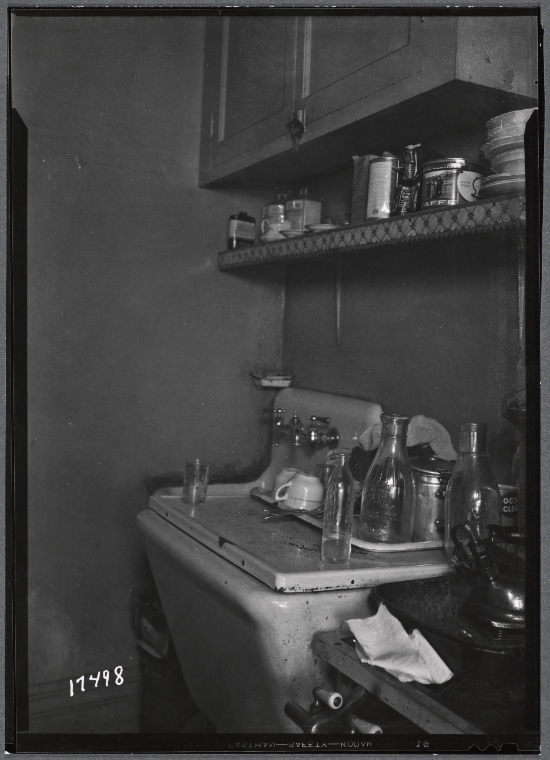

Little Italy tenement kitchen interior, 1937. Note the can of Italian “caffe” on the shelf in the upper right. Courtesy of New York Public Library.

And what about the Irish Moore family that lived at 97 Orchard Street in the 1840s? In Irish culture it is tea rather than coffee that prevails. Louise More’s (1910) breakdown of an Irishman’s budget for a family of ten included: “One-half pound tea; no coffee $.20.” Reformers of the time called Irish women “tea inebriates.”

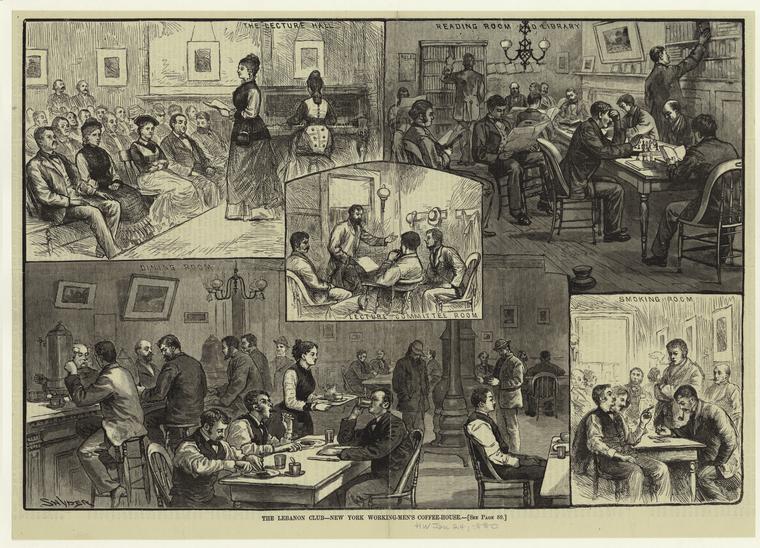

Likewise, Russian and Polish Jews such as the Levines and Rogarshevskys who lived at 97 Orchard Street preferred tea to coffee. They drank tea in cafés by putting a sugar cube in their teeth and then sucking the tea through it. They would drink dozens of glasses of tea this way, late into the evenings. And there’s an interesting contrast between the Irish and Jewish drinking habits: Irish immigrants drank tea at home and liquor in public spaces, while Jews drank liquor at home with family, and tea in public.

—Posted by the Museum’s Education Team