Blog Archive

The Lower East Side and Chinatown

June 5, 2014

After last night’s Tenement Talk with Jack Tchen, co-author of the book Yellow Peril! We’ve been considering contemporary anti-Asian discrimination and its repercussions. In this week’s blog Tenement senior educator Adam Steinberg brings us some text and context for the history of the Asian populations in the Lower East Side:

This novelty postcard is a apt metaphor for New Yorker’s early conception of Chinatown. This postcard portrays an exotic perception of the New York neighborhood. Image courtesy of the New York Public Library.

“When did the Lower East Side become part of Chinatown?”

For many visitors to the Tenement Museum, the Lower East Side is – or, at least, was – a Jewish neighborhood. When they think of the Lower East Side, they envision bialy bakers and tallis makers. But then they visit our neighborhood and see store signs in Chinese, not Yiddish, and shops selling dumplings, not pickles. What happened?

I always try to steer people away from thinking of the Chinese as “taking over” the Lower East Side. No neighborhood belongs to any one group, and a wide variety of communities has staked a claim to this corner of Manhattan over the years. In my head, I can hear the Germans in 1880s revisiting their old neighborhood and asking, “What happened to our beloved Kleindeutschland? Where did all these Jews come from?”

In fact, the Chinese were in Lower Manhattan longer than most anyone. Before the Civil War, increasing trade with China brought a small group of Chinese immigrants to Five Points, the neighborhood that once stood north of City Hall. But it was the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad in 1869 followed by increasing violence against Chinese immigrants throughout the Western United States that brought a surge of Chinese migrants to New York City.

Perhaps Chinatown, as it came to be called, would have continued to grow much as the Jewish Lower East Side did, but in 1882 the U.S. government, under pressure from organized labor and Western politicians, passed the Chinese Exclusion Act. This law all but banned immigration from China to the United States. It remained in effect until 1943, when, as a sop to our new ally in our war with Japan, the federal government replaced it with a yearly Chinese immigration quota of… 105 people.

Finally, in 1965, the federal government replaced the national quota system with our current immigration system, setting up New York for a surging influx of Chinese (and many other) immigrants.

For the Chinese immigrants arriving after 1965, Chinatown made perfect sense as a first home in America. The tenements, though overcrowded and often substandard, were close to jobs and Chinese cultural institutions. Although it was not the cheapest neighborhood in the five boroughs, immigrants have long paid a premium to live near each other. Few experiences are more disorienting than being a new immigrant in a foreign country where you don’t speak the language or understand the culture. If I found myself immigrating to a foreign country, especially if I had no money, I’d do whatever it takes to live among people who speak English, at least at first.

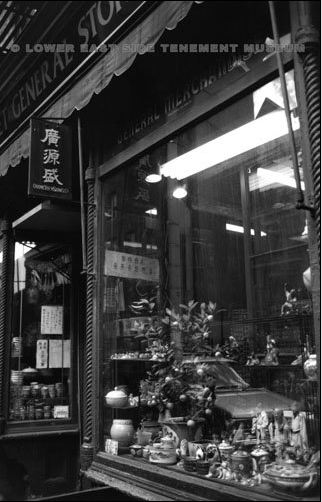

Chinese language signage has long been an indication of Chinatown’s parameters however, Kleindeutschland could once have been measured the same way with German language signs stretching as far north as the Ottendorfer Library off East 8th Street.

Although the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 opened the doors to these immigrants, two events in Asia would enable Manhattan’s Chinatown to spread far beyond its traditional borders.

First, the Communist government of the People’s Republic of China decided to experiment with capitalism. Starting in 1979, the central government opened up China region-by-region to outside investment and private property ownership. Formerly agricultural societies were transformed, and millions of young people began migrating to large cities throughout the world looking for work. Many of these immigrants ended up in Manhattan’s Chinatown, swelling its population.

Second, in 1985 the British government signed an agreement with China ending British control of Hong Kong in 1997. Successful entrepreneurs in Hong Kong, fearful of what a new Communist government might do to their assets, began looking for places to invest their money. And as has been true for more than 200 years, few investments are considered as safe or as profitable as Manhattan real estate. These Hong Kong entrepreneurs naturally gravitated to Manhattan’s Chinatown, where potential tenants shared their language and culture. As they bought up surrounding properties, they tended to rent to the growing number of Chinese residents and shop owners.

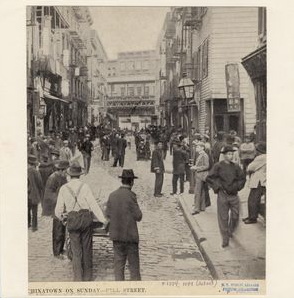

This historic view of Pell Street was photographed in 1899. While Pell Street is still within today’s Chinatown, many areas of historic Chinatown are now being developed for high-cost condos and galleries. Image courtesy of the New York Public Library.

What does the future hold for Manhattan’s Chinatown? Despite its prominence, it may be past its peak. With property values in Manhattan continuing to rise, more and more newly arriving immigrants find their first home in the new Chinatowns of Brooklyn or Queens, not in Lower Manhattan. And many of the businesses that once served the Chinese immigrant community in Lower Manhattan have been replaced by shops catering to the tourist trade or even the growing population of “hipsters” eager for artisanal foods, boutiques, art galleries, and coffeehouses. Perhaps in a few more years, visitors to the Tenement Museum, walking past Lacoste boutiques and Michelin-starred restaurants, will ask, “When did Chinatown become part of SoHo?”

– Adam Steinberg, Senior Educator