Blog Archive

Stories Yun Told Me: Simplified Character

“Stories Yun Told Me” is a series of illustrated stories created by Tenement Museum Educators Jason Eisner and Ya Yun Teng. The series will explore themes of language, interpretation, memory, and community through the adventurous eyes of Yun, a fictitious Chinese American immigrant born in the year of the Pig. At twenty-two, Yun immigrates to New York City from her native Taiwan. She loves to share stories about her experiences—stay tuned for further installments!

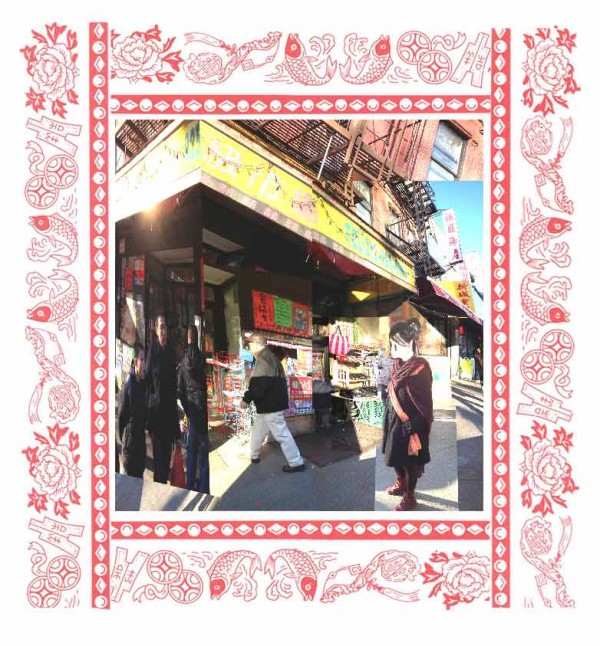

I found myself heading towards East Broadway to visit a new Chinese community. They call East Broadway the Fuzhou Street because there are so many immigrants from Fujian province living there. Coming here much later than the Cantonese, the Fujianese established their own community across the Bowery from Mott Street, creating and expanding along East Broadway.

I have never been to Fujian, but some of my family members, if I trace far back enough, came from there. Compared to Canton, Fujian is much closer to Taiwan in many ways. If I were a good swimmer, I could swim across the Taiwan Strait to get myself to Fujian (the shortest distance is 80 miles).

I passed by the gift shops of Mott Street with their Chinese lion puppets dangling from awnings, and leaped across Bowery to East Broadway. The tenement buildings were not so different from those around Mott Street. But on the street there was a young and thriving energy.

Only some stores maintained the old-fashion signage which had a look from the 70s. But popping up in every other storefront were newer grocery stores and restaurants that served Fujianese rice noodles and fish balls. Many ground floor tenement storefronts were re-modeled, with big glass windows and doors with stainless steel handles. Although everyone loved the light brought in by the windows, the vendors soon covered them up with sale announcements to compete with other stores in the mall. Most of these signs were printed in simplified characters.

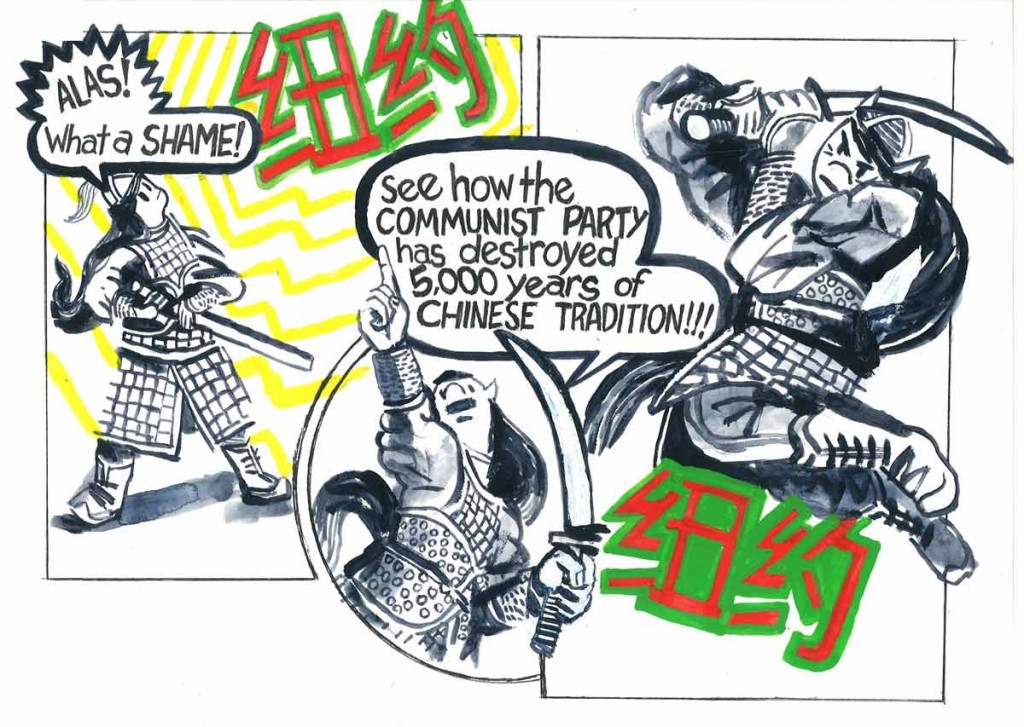

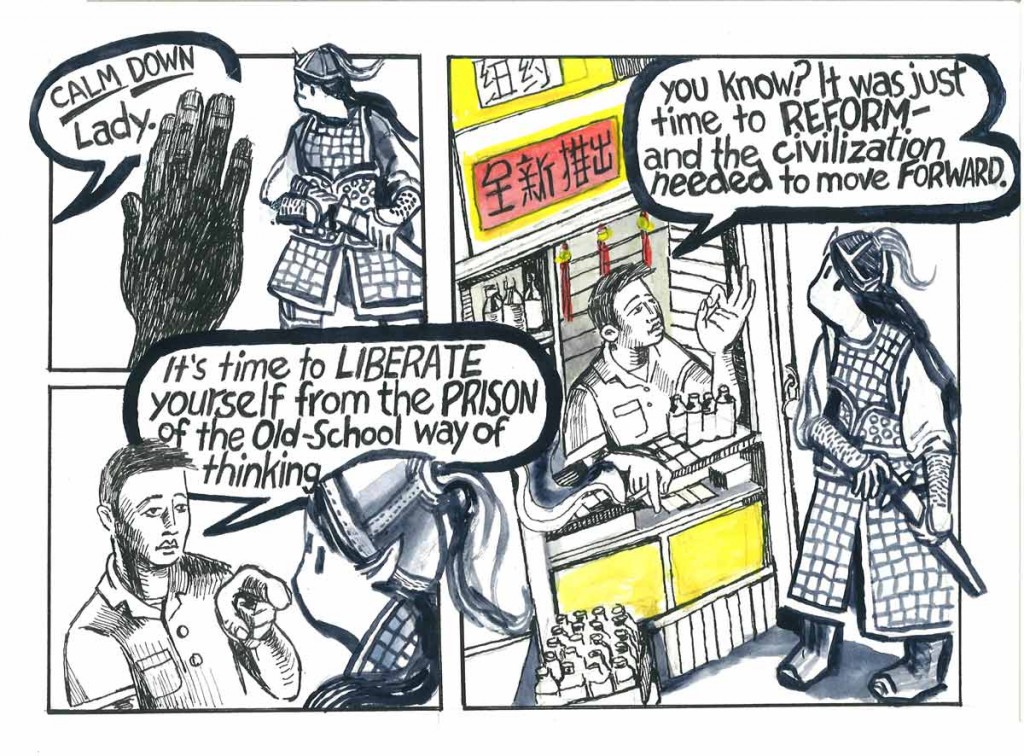

I was not used to seeing simplified characters in public spaces while growing up in Taiwan. After the Communist Party established the new government, many changes came to China. Even the language was revolutionized. The Communist party did away with the traditional character form and began teaching simplified characters schools. This was done to increase the rate of literacy, and eliminate the gap between rich and poor. But in the eyes of the Taiwanese government, replacing traditional characters with simplified ones would result in permanent damage to the Chinese culture and language.

As someone growing up in Taiwan, a country ruled by the Conservative Nationalist Government established by Chiang-Kai Shek (who miserably lost his battle to the Communist party in 1949), it was probably my duty to defend my tradition.

But I didn’t get a chance to do that–I felt like there wasn’t even a part for me to play. I was just an outsider walking through Fujianese Chinatown.

When I visited Mainland China in the 90s, it was the first time I was surrounded by simplified characters. I stuck close to my mother, and my mother stuck close to the other travelers from Taiwan, and all of us stuck with our tour guide. This was the first time since the Chinese Civil War that Taiwanese were allowed to travel to China. There were so few of us, and we felt vulnerable.

Along with our clothes we packed our imagination of Mainland China. We were looking to verify our long held beliefs. We imagined the Chinese on the Mainland lived behind the iron curtain, and grew up eating tree bark. Of course, we didn’t find any evidence of that.

Meanwhile, East Broadway was hustling and bustling.

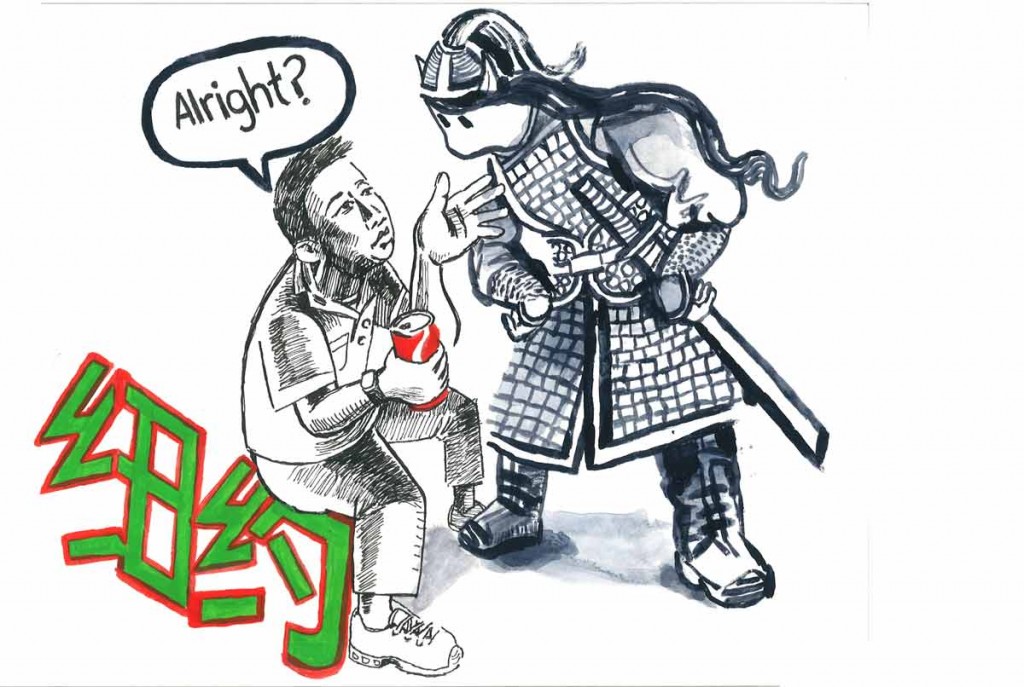

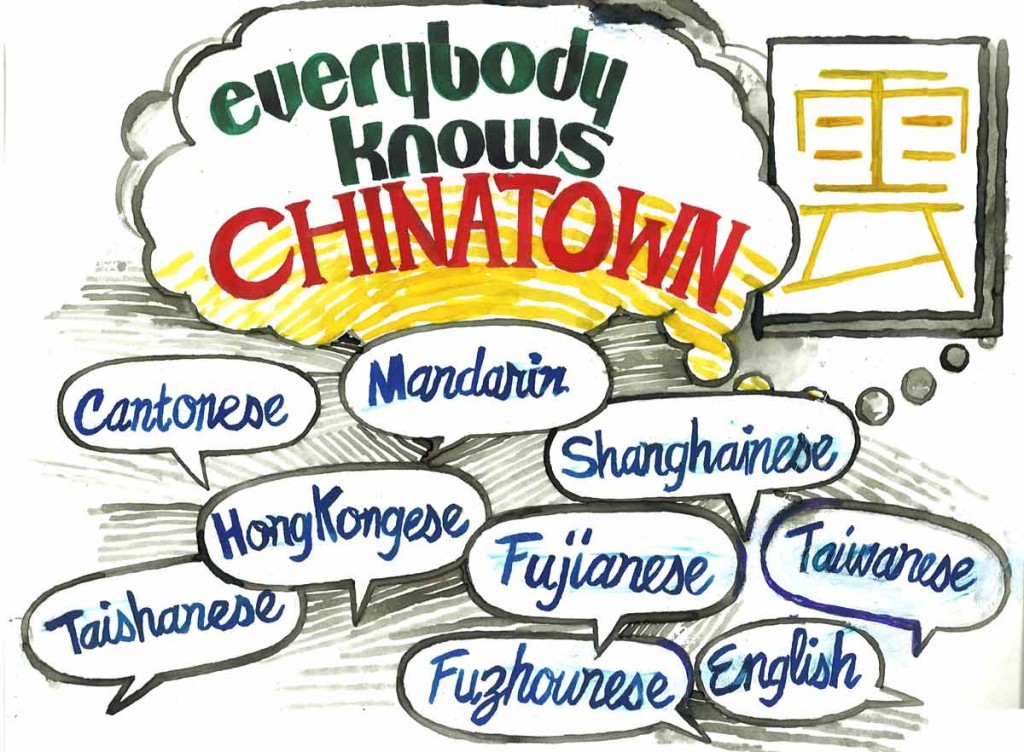

Two children were on their way back home from school. In their hands, they held some orange and black Halloween decorations they made as school projects. They were with their mother. The elder sibling was using English to comment on the more primitive-looking quality of the younger sibling’s project. The younger one seemed hurt. All this time their mother was talking to someone working in a market using a language I could not understand. It didn’t sound like Cantonese to me, and it was definitely not Mandarin. Maybe it was Fujianese? My family spoke Taiwanese, which originated from Southern Fujian. I was trying to find some words that I could recognize, but their language sounded very far away from any languages I knew.

I realized that the man she was talking to was a phone card salesman. He started to speak to the mother in Mandarin, a language I grew up speaking, but his accent was totally unfamiliar. He used his chin to point at the children and said, “They are so big now. How many years you’ve been living here? Have you been back home? They speak so well, like American now.”

I stopped walking and moved closer, just to listen to the song of their accent – a piece of music performed with a new and unexpected interpretation. I thought I could sing along, but failed to follow the beats. A workingman with loads of fruits and vegetables asked me to step aside. The market was filled with people singing their languages and picking groceries for dinners tonight. East Broadway rolled along…

— Posted by Jason Eisner and Ya Yun Teng