Blog Archive

Stories Yun Told Me: The Professional

“Stories Yun Told Me” is a series created by Tenement Museum Educators Jason Eisner and Ya Yun Teng exploring themes of language, interpretation, memory, and community through the adventurous eyes of Yun, a fictitious Chinese American immigrant born in the year of the Pig. At twenty-two, Yun immigrates to New York City from her native Taiwan. She loves to share stories about her experiences—stay tuned for further installments!

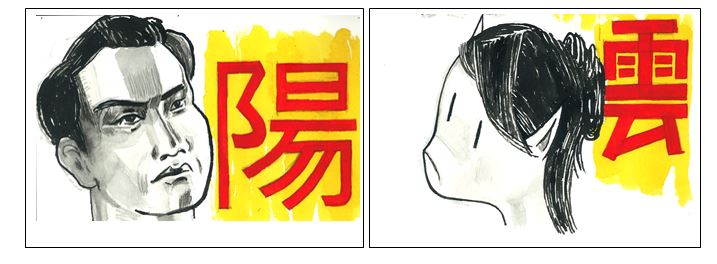

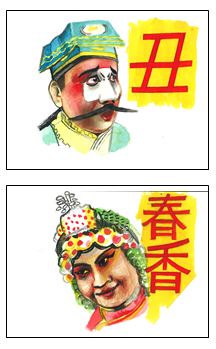

I was standing in a Manhattan children’s library, watching Yang perform his Chinese opera demonstration surrounded by a giggling young audience. He was a clown- a role he specialized in. His mask was a small white patch of makeup in the middle of his face and when he blinked his eyes, waves of laughter burst out from the little ones.

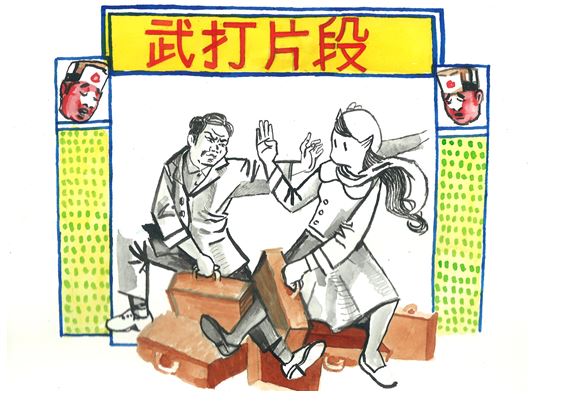

The Opera finished and Yang’s new fans went home with their parents or returned to their computer screens. The library rock star was left alone packing. He emerged from the public toilet with water drops on his cheek- a trace of his clown make-up was hanging on. I picked up a bag filled with costumes and walked with him towards the subway station, but he snatched it back.

“A man shouldn’t let a lady carry a bag for him!” Yang was proud. Whenever he did this in the past there was always a team of us around. We applied peer-pressure and eventually Yang had to give up his bags. Today it was just the two of us and Yang took his revenge. “No matter what kind of rule we have here or on Mars, I am following my own rules.” I pulled at the bags but he ignored and started to step forward. We almost had a battle.

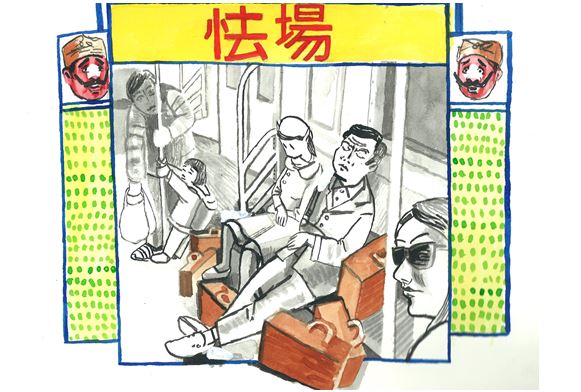

On the train, Yang didn’t speak to me. He closed his eyes but didn’t nap. His face hardened into a mask with dark circles under his eyes. I was going to ask him what he thought of the library performance, but after our battle, I felt reluctant. Anyhow, I had already heard him complain about this kind of performance, or more generally, problems of performing in America.

“It is boring to perform for a group of people who know nothing about the art.” He once confessed, “I didn’t even try to do my best on the stage. No one would notice it, so what’s the difference?” Sometimes he lamented, “No one cares about authenticity. They only laugh at the cheapest things I do.”

We became friends even though Yang always made fun of me and tried to provoke fights, “I am not like you. I didn’t go to college. I spent all my life with old-fashioned opera troupes,” he emphasized the word “old-fashioned”. He said this as he adjusted my arm position and twisted my waist to an almost painful point. I was learning a classic opera from him. He continued his lecture,” Tell me how many Taiwanese college graduates like YOU know their Chinese opera tradition?” He fancied himself a trickster, “I guess you still know better than those Chinese raised in America.”

When he saw my arm slip back to the old position he said, “It would be alright for someone like you to perform Chinese opera in America.” Then tapping my arms, “Those people know nothing about the art, anyway.”

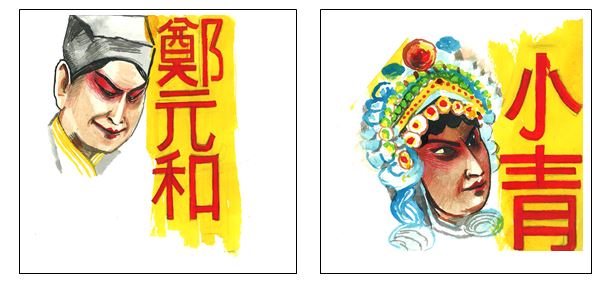

For Yang, Peking Opera was everything. Because Chinese government subsidized traditional arts, his poor parents sent him to a Peking Opera Academy near Tianjin, hoping for a stable future. Yang had a glamorous landing in the United States. He was invited to Lincoln Center as a guest Chinese opera performer. Soon afterwards, he got a green card as an “extraordinary individual”, while his fellow opera performers were still scrambling to collecting materials for their applications.

Yang was in control. He was dedicated to his art and he cared about his tradition. He believed that it should be preserved that way he learned it. He spent hours in a studio every day to maintained good physical condition.

Things drifted out of control when the Lincoln Center gig ended. He remained optimistic, but began to see his fellow opera friends starting to pick-up work in restaurant and construction, or driving busses. His heart was torn, and he would lecture them like he did to me, “Don’t you guys dare to forget what you were born and trained for.” They replied, “No one has interest in Chinese opera, and artists here survive by picking up other jobs.”

Soon Yang found himself washing dishes in a restaurant and moving boxes in a warehouse. In the mirror Yang saw a new mask reshaped by his work. His body felt constantly achy and sore, very different from the physical training he was used to. Not too long ago, an opera friend who owned a nail salon took him in. Yang’s face-painting skills proved useful for painting intricate patterns on customers’ nails.

The train rocked violently. Yang opened his eyes. We were close to the station where Yang had to work. He gestured to the bags. Yang was relying on me to return the costumes, since he had to work.

“Thank you for carrying the bags,” Yang didn’t wear any masks when he said so.

– Posted by Jason Eisner & Ya Yun Teng