- Post by Gemma Solomons, Marketing & Communications Coordinator at the Lower East Side Tenement Museum

Blog Archive

Returning to the Scene of the Crime

DISCLAIMER: Some of the photos below contain graphic imagery and may not be safe for work.

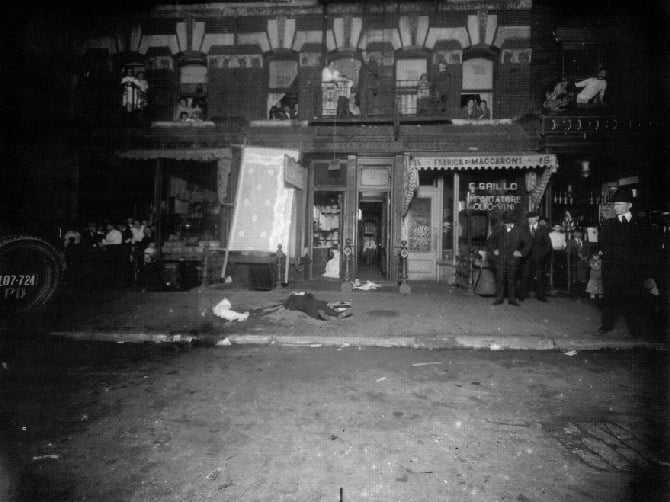

“19305 undersize.” Sante speculates the photo could possibly be in lower Manhattan. “The killing might have been in connection with a robbery or an argument on the street, although the open door of the laundry on the left…suggests something beginning inside the store and spilling out.” Photo from Evidence by Luc Sante.

Luc Sante was doing research for his 1991 non-fiction novel Low Life: Lures and Snares of Old New York at the Municipal Archives, when an employee offered to show him the New York Police Department Photo Collection. What Sante found would eventually lead him to publish another book entitled Evidence: NYPD Crime Scene Photographs 1914-1918, which in turn were later used by the Lower East Side Tenement Museum for curatorial purposes.

The history behind the crime scene photos found by Sante is interesting, and a little heartbreaking. The box he was given was a disorganized mishmash of photographs, memos, and paperwork. They were rescued by city archivists sometime around 1983 or 1984, when an old police headquarters had been resold for private use, and workers had taken roomfuls of files and dumped them into the East River (which, for some history buffs reading this, might be the most horrifying thing about this entire article). But a small room beneath a staircase had been overlooked, where archivists found filing cabinets, neglected for nearly 75 years, presenting a snapshot, if you will, of New York City at its darkest moments.

It is hard to look away from Sante’s discovery. The collection varies, some depicting the aftermath of a violent crime in graphic detail: the blood stains, the signs of struggle, the faces frozen in pain or fear – or some merely show the surrounding area: the curious witnesses, the grim faces of police officers, the possible clues of which their importance is now long forgotten. Both are evocative in their own way. The gruesome deaths are perhaps not as bad as what pop culture has desensitized us to, except when the dawning realization hits that what we’re seeing is completely real. But the empty photographs are just as horrible in what they’re able to imply. “Empty photographs have to reason to be,” Sante wrote in Evidence, “except to show that which cannot be shown.”

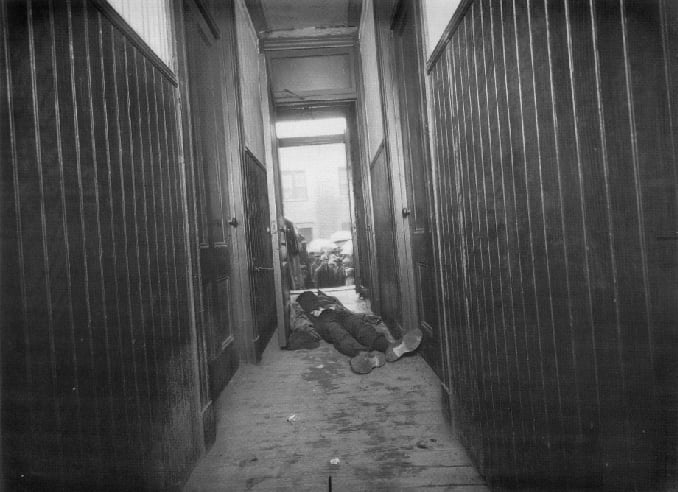

No caption. The body is lying in the front hallway of a tenement. Sante: “A crowd has gathered outside, in the rain, holding umbrellas. The cigarette butt on the floor might have been thrown there by anyone, including the cops.” Photo from Evidence by Luc Sante.

“Homicide (female) 1917 (undersize) #1724 6/24/17” Sante found a corresponding newspaper article with the headline “Girl Slain, Man Shot In Joy Ride – Cabaret Singer Is Killed When Three ‘Friendly’ Strangers Attack Her Sweetheart.” Photo from Evidence by Luc Sante.

Nearly all of the 1,400 plates of forensic photography found beneath that staircase had no caption or detail, all significance lost except for what clues could be deciphered in the photographs themselves. One can look at them out of morbid curiosity, and then maybe only at a momentary glance – or one can look at them out of respect for their surprising artistic quality, detaching oneself from the true nature of the subject. “I am presenting [the photos] because of their terrible eloquence and their nagging silence,” Sante wrote. “I cannot mitigate the act of disrespect that is implicit in the act of looking at them, but their power is too strong to ignore; they demand confrontation as death demands it.”

The Lower East Side Tenement Museum, however, saw their implicit value as a window into the past. The Museum itself operates as that window, inviting visitors to climb through, and prides itself on the authenticity of what lies inside. Though none of the Museum tours walks its visitors through a crime scene, the everyday details inside each photograph that were practically banal to the people when the pictures were taken, but for historians, curators, and archivists they’re a priceless glimpse into the actual.

Specifically, the time period of the photos lines up perfectly with one apartment, belonging to the Rogarshevsky family in the early 1900s, as viewed on our Sweatshop Workers tour. “What’s useful about these photos,” said Tenement Museum curator Dave Favalaro, “is that, unlike similar images captured by reformers like Jacob Riis, the crime scene photographers did not have 1) an agenda in trying to depict a certain set of conditions; the worst of the worst, to galvanize public support for house reform and 2) the crime scene photos are, in a morbid way, much more spontaneous than similar photos taken by reformers.” Often reformers like Riis would stage photographs to provoke the most outrage and garner the most change for those in abject poverty, which was a worthwhile goal. But the residents of 97 Orchard Street were working class families, who typically weren’t living in squalor, so finding accurate visual representations of their living conditions proved to be challenging.

“Killed by William Burke at 140 W 32 on 1/22/16 DeVoe file #1002.” Sante could not find any other information about this crime, but noted: “Much can be gleaned about the subject’s life in this photograph, but little about his death.” Photo from Evidence by Luc Sante.

No caption. The white circle is the result of plate damage. The photo of a yard often found in the middle of tenement blocks reveals the garbage of the day but no clues of its purpose. “It is not, for example, inconceivable that this could be the site of the July 1916 murder to which the perpetrator called attention by drawing an arrow on the sidewalk in his victim’s blood.” Photo from Evidence by Luc Sante.

When someone died inside their home, however, the police weren’t going around straightening up the place or rearranging the furniture. So the decor, the furniture, the arrangements, were as true to life as one can get, in a scene of death. “The crime scene photos are therefore a much more ‘authentic’ depiction of tenement interiors from this period,” Favalaro said. So we grit our teeth, study the dead, leave out the blood splatter and take note of what’s on the dresser.

Photography is such an effective and provoking medium because it holds forever still a moment in time – a moment now long gone. One can look at a photo from 1918 and assume everyone in it has passed away, but, as Sante explains it, even a photograph – of a dinner, a portrait, a nature hike – now only exists in the past. The food’s been eaten, the smile’s been dropped, the bird has flown away. As Sante put it, “Every photograph is haunted, and….is the occasion of a haunting.”

No caption. According to Favalaro, this photo was the basis for restoring and recreating the Rogarshevsky apartment. Photo from Evidence by Luc Sante.