Blog Archive

Refugee Blues: Hannah Arendt

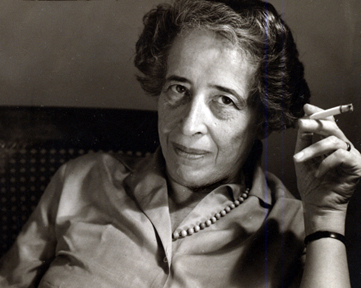

Hannah Arendt: a refugee of Fascism who helped to shape Post-War thought about the violence of the twentieth century. Image courtesy of the Hannah Arendt Center at Bard College.

Saw a poodle in a jacket fastened with a pin,

Saw a door opened and a cat let in:

But they weren’t German Jews, my dear, but they weren’t German Jews.

–From “Refugee Blues” by W.H. Auden

Immigration to the Lower East Side has been a complex tug of war. Each wave of immigrants has negotiated their share of push and pull factors depending on their country of origin and the time of their departure. In the late 1930s, violence in Europe and Asia caused shockwaves of tension in many corners of the globe. Many immigrants attempted to flee Fascism just as military measures made boarders impenetrable.

One of the luckier refugees of the violence was a brilliant German-Jewish philosopher named Hannah Arendt. In order to become “lucky”, Arnedt had to have the resources to recognize the seriousness of fascism in Germany and to find a way to arrive first in Prague and then Geneva and then Paris. Finally in 1941 she found a way to enter the United States: New York City. Arendt brought with her some of the most lasting analysis of Fascism and Stalinism to arise in the post-war period. As a result, theorists, historians, professors and film-makers continue to honor Arendt to this day.

Arendt was born in Hanover, Germany in 1906 to a family of ‘secular’ German Jews. Her education reads like a who’s who of preeminent German philosophers at the time. In 1926, after completing high school she attended Marburg University where she studied under Martin Heidegger, one of the most highly-regarded minds of German philosophy. Heidegger recognized in Arendt another bright mind and their relationship quickly became a “brief but intense love affair.” Arendt was just getting started. Soon she moved to Freiburg and spent a semester attending the lectures of Edmund Husserl another widely respected philosopher. After Freiburg, Arendt moved to Heidelberg to study with Karl Jaspers in the spring of 1926 and began an important intellectual relationship which lasted for years.

After completing her doctoral dissertation on St. Augustine’s ideas of love in 1929, she worked for a German Zionist organization in a climate of increasing toxicity for Jewish Germans. That same year Arendt married Günther Anders who wrote under the name Stern, a fellow philosopher and thinker whom she met at Heidegger’s lectures. At the time, Arendt only had eyes for Heidegger, but when they met again at a ball in Berlin, Stern whispered a sweet treatise on love to marvelous effect [1]. Arendt was arrested and forced to flee Germany in 1933. When Arendt finally arrived in Paris she worked for six years for several Jewish refugee organizations. She had divorced Stern in 1937 and began a relationship with Henriech Blücher whom she met while working for Youth Aliyah an organization which helped Jewish youth escape internment in Europe.

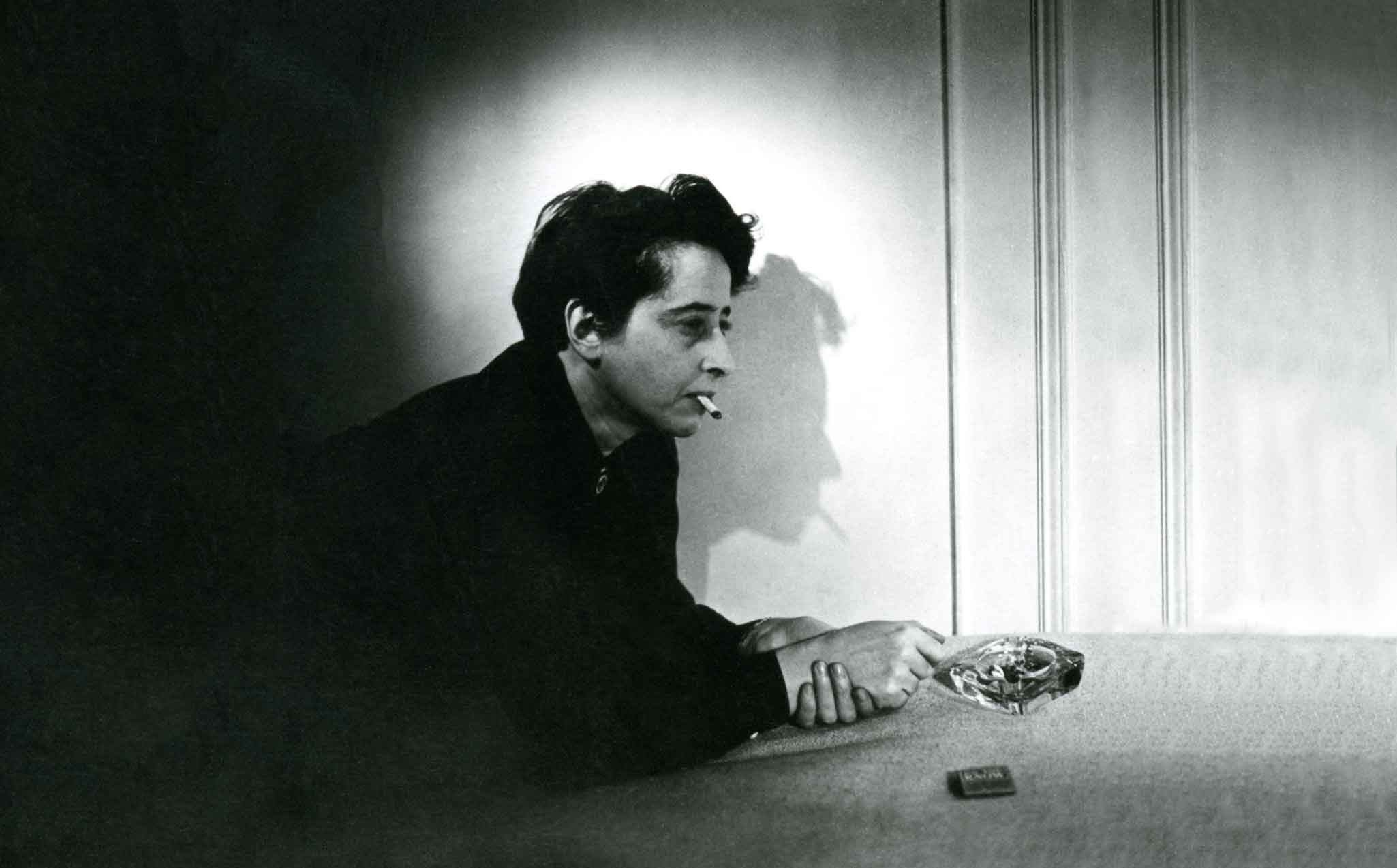

Arendt deep in thought. Image courtesy of the Film Forum.

She was imprisoned at Gurs detention center for her political ideas but escaped, walking and hitchhiking to as yet unoccupied territories of France where she encountered Blücher by chance. Hard work and brilliance had helped win her a certain renown and she had made the list of Varian Fry’s Jews to be saved. (Fry was an american journalist who, through forgery and Black Market maneuvers managed to get around 2,000 people out of Nazis occupied territories where they were wanted by the Reich.) In 1941 Arendt and Blücher managed to board a ship leaving from Lisbon and became two of the last Jews to leave France.

Once settled in the United States, Arendt lived on Riverside Drive in New York and worked as a writer, scholar and editor writing frequently on refugees and anti-Semitism through the 1940s. In the 1950s Arendt published two of her most important works, The Origins of Totalitarianism and The Human Condition which discussed the impact of modernity on the human condition and the impossibility of understanding tradition after the savage acts of Nazism and Stalinism.

In 1961, she covered the trial of Adolf Eichmann, a high-ranking Nazi commander for The New Yorker. When she concluded that Eichmann had committed millions to death not out of raging malice but out of a bureaucratic devotion to the regime, both Arendt and The New Yorker were at the height of their powers.

With her ever present cigarette. Image courtesy of the Hannah Arendt Center at Bard College.

Arendt was honored in the United States as a visiting professor at Berkeley, Princeton, Columbia and Wesleyan. After the death of her husband, the acclaimed poet Wystan Hugh (W.H.) Auden – who was openly gay – proposed marriage to Arendt as a display of their firm friendship. She did, however, refuse.

It is a testament to Arendt’s incredible intellectual powers that an extensive study in recent years have both undermined her theories about Eichmann, and reified her thoughts on modernity. Years after Eichmann’s trial, archives she could not have accessed have showed that Eichmann was much more intentional than Arendt at first believed, bringing her controversial claims to life again. Even popular audiences have welcomed portraits of Arendt. A feature film, Hannah Arendt, and a documentary have charted her dramatic and rich intellectual life. Vita Activa is the newest documentary about Arendt currently showing at the Film Forum through tomorrow, April 20.

–Posted by Julia Berick, Marketing and Communications Coordinator

Research for this blog was aided by the Hannah Arendt Center at Bard College , Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy and Humanities the Magazine for the National Endowment of the Humanities. Much more in-depth discussion of Arendt’s philosophies can be found at these sites and others.

[1] “I won Hannah [Arendt] at the Ball with a comment made while dancing, that loving is that act by which something aposteriori–the by-chance-encountered other is transformed into an apriori of one’s own life. –This pretty formula naturally has not been confirmed.” – Anders in his book The Cherry Battle, this quote was harvested from the blog of the Hannah Arendt Center at Bard College.