Blog Archive

Recipes for Remembrance: Victoria Confino’s Passover Seder

Passover (Pesach in Hebrew) is the ultimate food holiday. Unlike so many Jewish holidays celebrated in synagogue, Passover is observed at home, twice, by gathering around the table for a special ceremony, the Seder (literally meaning order), and enjoying a festive meal. The Seder is laid out in a book called the haggadah, which tells the story of the Exodus of the Jews from Egypt and provides prayers as well as explanations for some of the practices and symbols of the holiday. Intended to connect the Jewish people to the Jews of centuries past, the Seder encourages us to remember and to reenact the story of Passover with the indispensable help of several foods, mnemonic devices that symbolize everything from enslavement to sacrifice, freedom and renewal.

For the immigrant families of 97 Orchard Street and throughout the Jewish Lower Eastside, Passover Seders must have been especially meaningful. The themes of sacrifice, new beginnings, and freedom must have hit especially close to home for those who had recently left their own homes and all that was familiar in order to begin again in New York City. The meals that followed the service were likely more abundant than they had been in their home countries, but the tastes would have been bittersweet, reminding them not only of the Passover story, but also bringing back memories of homes they’d left behind.

Many generations later, most American Jews still perform the same ritual year after year, remembering the story of their people and channeling their family ancestors by cooking and eating the same recipes that they would have eaten. For most of them, Ashkenazi Jews of European descent, no Passover meal would be complete without chicken soup, matzoh balls, brisket, and even the most famous of acquired tastes, gefilte fish.

All over the Lower East Side of the early 20th Century, tenements like 97 Orchard Street would be buzzing with activity in preparation for these nights that are “different from all other nights.” Matzoh would be purchased, apartments scrubbed clean, and Seder plates taken out of storage. Tables would be dragged into parlors usually reserved for beds, coal fires would be lit in every cast-iron stove, and from most apartments, the rich, thick smell of schmaltz and chicken soup would waft out of open doors into the narrow hallways.

In 1916, the smells coming from the home of the Confino family, however, were different from those coming from the neighbors: there was the smell of eggplant baking with tomatoes and the nutty richness of huevos haminados, slow roasted eggs. There was the fragrance of leeks frying and fresh lemon juice, the sweet smell of honey syrup and cinnamon. Victoria Confino, 14, and her sister Allegra, 19, would be eagerly awaiting their yearly gift of a new dress from their brother Joseph as they helped Rachel, their mother, cook for the holiday. There was so much to do that perhaps even their three younger brothers would have been put to work. The Confinos, a Sephardic Jewish family from Kastoria, Greece, would be cooking their family favorites, dishes that most Americans Jews have never tasted: mama’s famous piskado, rolls of fish baked with tomato and spices; tiny albondigas, dense, marble-sized matzoh balls served in soup; fritadikas de espinaka, spinach and meat fritters stewed in lemon; and Victoria’s favorite, bimuelos, fritters steeped in cinnamon laced honey and sprinkled with toasted walnuts.

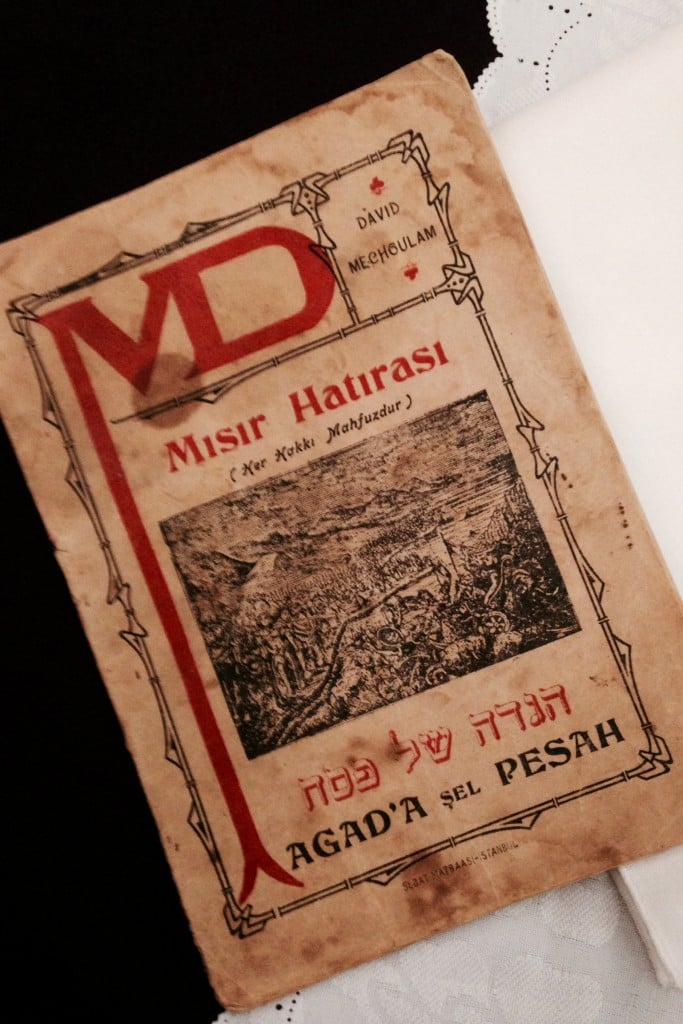

This year, 99 years after the Confinos celebrated Passover at 97 Orchard Street, the costumed interpreters whose job it is to bring Victoria to life for visitors, met to recreate the Seder Victoria and her family must have had three years after arriving in the United States. We gathered at the museum where Miriam Bader, The Museum’s Director of Education, and Jessica Varma, head of Costumed Interpretation, were our Mama and Papa for the evening. They led us through the service as it was laid out in an old, brittle, and stained Ladino version of the Hagaddah, our prayer book for the evening.

We learned about the traditions that Sephardic families like the Confinos would have had: kissing Papa’s hand as he returned from synagogue, the youngest boy marching out into the hallway, matzoh on his shoulder, to lead the others on an exodus to Jerusalem, and the Ladino songs that Victoria, a lover of singing, would have sung, even if she and Mama had excused themselves from the table to clean up as the men concluded the Seder service while enjoying their Turkish coffees and after-dinner digestif .

Those of us who had been to Seders before learned the differences between what the Confinos would have done and what we were familiar with: celery and vinegar replace parsley or potato and salt water, the four questions are read by all in unison, the afikomen never gets hidden at all! We compared and contrasted, looking for similarities, learning the stories behind the differences, all the while laughing, enjoying one another’s company, and feasting, just as the Confinos would have done.

Our meal was a potluck, each of us preparing one of Victoria’s own recipes, handed down to us by her granddaughter and great niece. Most of us spent the day cooking at home on our own, a far cry from experiencing the hubbub of 97 Orchard Street on the eve of Passover. Nevertheless, we cooked to remember a family we honor, to experience a small piece of what generations of Confino women would have experienced as they chopped and sautéed, tasted and tweaked.

Food writer Laurie Colwin famously wrote, “No one who cooks, cooks alone. Even at her most solitary, a cook in the kitchen is surrounded by generations of cooks past…”. Food and cooking can be powerful tools for conjuring memories. For Jews on Passover, food is a tool for connecting to the Jews of thousands of years ago by simulating the experience they had as they fled toward freedom. For us, it also became a way of communing with an immigrant girl who lived one hundred years ago, a girl whose story we at the museum endeavor to tell as faithfully as we can. None of us will ever truly know exactly how life felt for Victoria Confino in 1916, but after our Passover Seder, our bellies full of the food cooked using her very own recipes, we have bit of a better idea.

– Post by Emily Halpern who is a costumed interpreter and educator at The Tenement Museum. She is also the creator of The Repast Project , a blog about preserving heritage through food.