Blog Archive

Looking at the Great Migration

The first panel of Jacob Lawrence's Great Migration Series. Each panel features a caption written by Lawrence. This panel reads "During World War I there was a great migration north by southern African Americans." © 2008 Estate of Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. This image courtesy of MoMA.

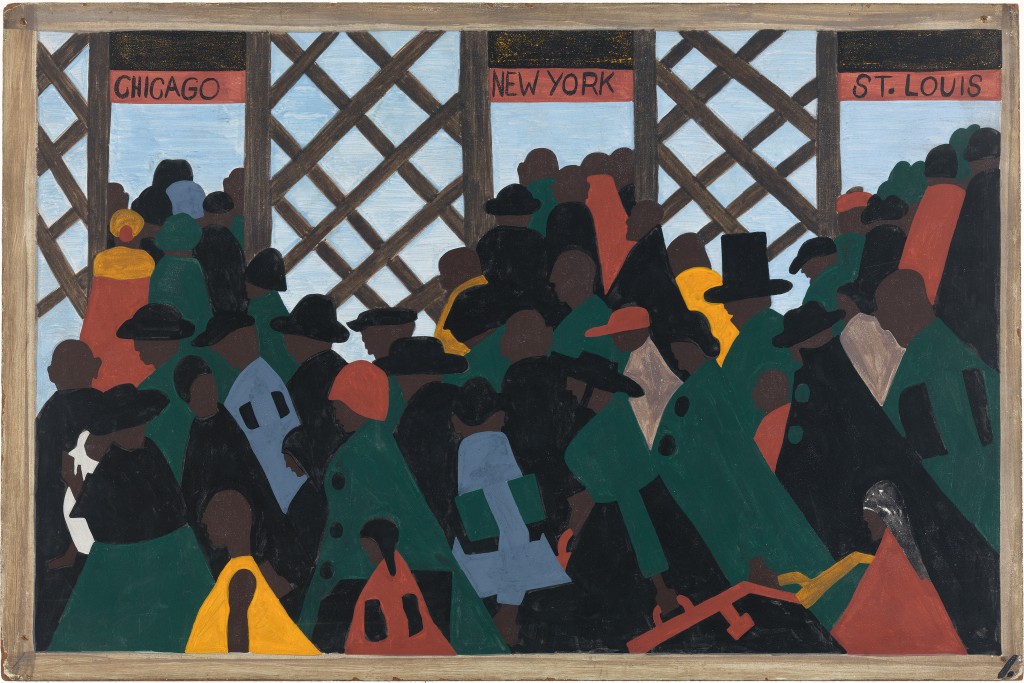

There is one tale of American Migration that is so different from the rest, that it seems at first to bear no relation to the stories we tell at the Museum. This is the Great Migration, the immense movement of African Americans from the rural South to the cities in the Northern and Western United States, including, of course, New York City. Unlike the other newly-arrived New Yorkers we discuss, these new arrivals were not immigrants. However, they left a place where their personhood was at risk and traveled hundreds of miles to a place where they hoped their American dreams would come true. Some of these migrants had their hopes realized, while others’ hopes were deferred and are still. As one of the largest demographic shifts in American history, the Great Migration is an essential chapter in the history of our cities and our country. What can we learn about this unique movement that can also help us understand immigration and the face of our cities today?

Historians consider the Great Migration to cover the movement of African Americans from around 1915 until about 1930. Though African Americans in the South had gained emancipation after the Civil War, they hardly gained equality. Georgia established its first streetcar segregation law in 1891. This was only the first legal measure of that era enacted by southern state governments to assert what many felt – that Americans of color were not deserving of equal protection under the law. By 1915, all Southern states had segregation laws of some sort, which historians now refer to as Jim Crow laws. Humiliated, threatened and killed because of the color of their skin, southern black Americans moved to the north hoping for jobs, opportunities and respect. While southern states rejected their black population’s personhood, they were loath to lose the labor force they represented. African Americans who held train or bus tickets were often intimidated or arrested; trains were prevented from stopping if it seemed that a great number of African Americans were boarding for the North. Pulitzer prize-winning journalist, Isabel Wilkerson, who wrote a history of the Great Migration The Warmth of Other Suns, found that though economists often speak of soil exhaustion and the boll weevil (a pest that preyed on cotton plants) as “push factors” encouraging black Americans to move north, not a single one of the 1,200 people she interviewed mentioned this phenomenon.

The jarring change between the rural south and industrial urban north was a move that, for some was almost like embarking upon a foreign land.

Panel 45 " The migrants arrived in Pittsburgh, one of the great industrial centers of the North." © 2008 Estate of Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo courtesy of the MoMA.

Once they arrived in Northern cities, hardships hardly ceased for this population. White populations living in the North and the West were often just as racist as their southern counterparts, even if these feelings were not codified into law. Arriving with little or no resources, Southern Blacks were often forced into substandard housing conditions and were at the mercy of manipulative employment practices. These newcomers also encountered some apprehension from Americans of color who already lived in Northern cities.

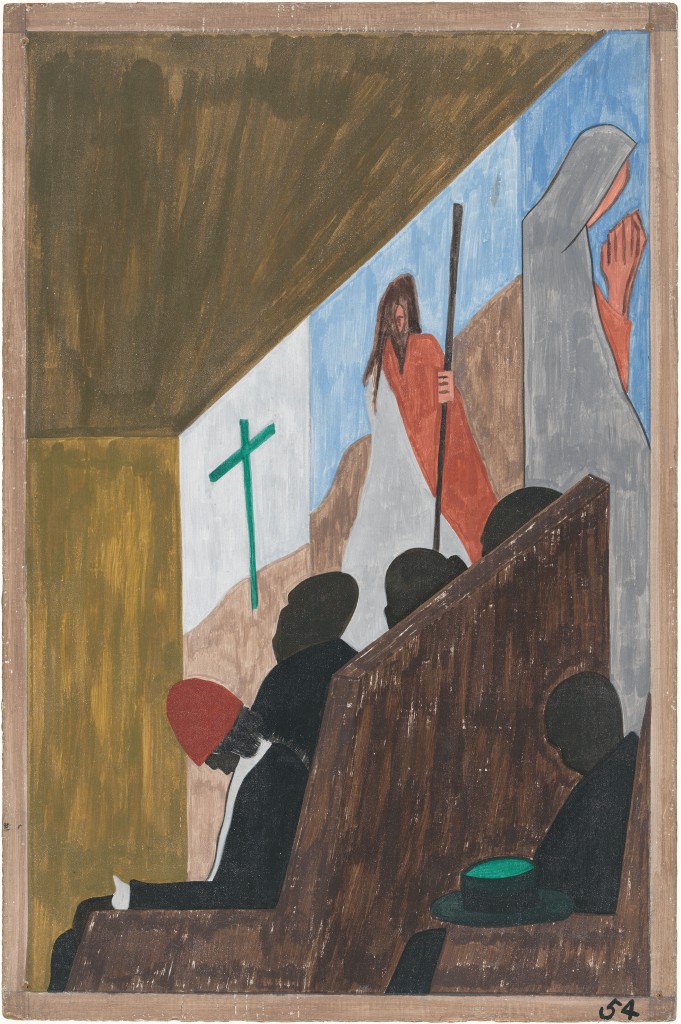

Much like between the German-Jewish immigrants who arrived first and the Eastern European immigrants who came later, African Americans who already lived in Northern cities were concerned about how such vast numbers of rural newcomers would change they way they were viewed by white society. Also, like some of the immigrants we discuss, this first generation of migrants had the sensation of “losing their children” to an urban culture in which they never quite felt at home. Wilkerson writes “The streets, with their noise and flaring lights, the taverns, the automobiles, and the poolrooms claim them, and no voice of ours can call them back.” Like the populations who lived on the Lower East Side, Southern Black populations living in the North and West often formed social clubs and churches which reminded them of home. Wilkerson reports that there are Lake Charles Louisiana Clubs in Los Angeles and churches in New York where all the congregations came from North Carolina. Feelings of alienation for these migrants and their descents , however, have lasted into the 21st century due to a myriad of biases held still held nationwide.

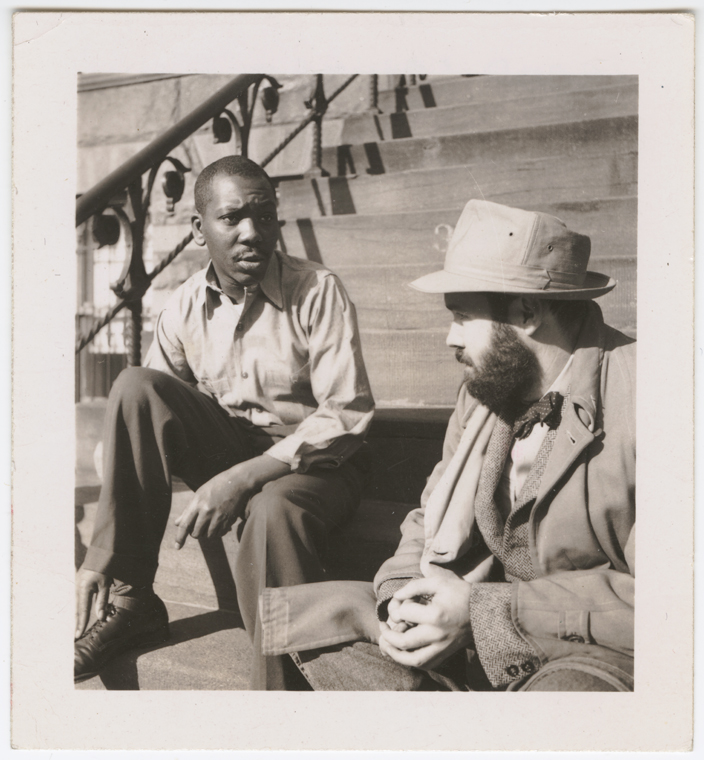

Jacob Lawrence in 1941, the year the Migration Series was completed and immediately recognized and collected by MoMA and the Philips Collection as a major artistic achievement. Photo courtesy of the NYPL.

We are fortunate to have a few very important records of the unique experience of these migrants. Some of our best American writers and artists became part of the Work’s Project Administration. It was as a painter in the easel division of the Works Project Administration that Jacob Lawrence began work on one of the most valuable records of this movement. On view now at the Museum of Modern Art for the first time in 20 years, Lawrence’s Migration Series is an epic collection of 60 panels depicting the themes and episodes of the mass migration. Do not miss the opportunity to consider Lawrence’s work and this chapter in American Migration.

–Posted by Julia Berick, Marketing and Communications Coordinator