Blog Archive

“Let’s Get Drunk and Make Love”: Lois Long and the Speakeasy

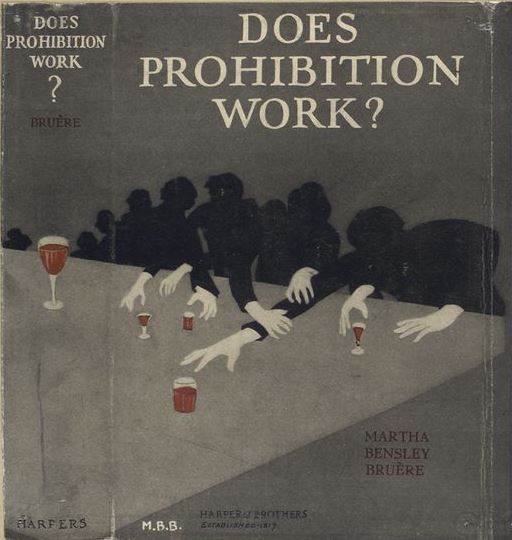

The debonair attitude characteristic of the prohibition, captured in this 1920s cartoon by Russell Patterson. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.

On January 17th, 1920, when Prohibition became the law of the land, a new kind of woman was born; a woman who drank, smoked, and (gasp!) danced with members of the opposite sex in illegal watering holes known forever as “speakeasies.” No one, man or woman, described these dens in such delicious detail as The New Yorker magazine’s cabaret-reviewer and resident dancer til dawn, “Lipstick.” “Lipstick,” nom de plume of Connecticut-born Lois Long, was one of the original New Yorker contributors, along with such famous writers as Dorothy Parker, E. B. White, and Alexander Wollcott, and outlasted nearly all of them – her career at The New Yorker spanned nearly 45 years.

At age 23, Long began writing her column, “Tables for Two”,” reviewing nightclubs across the city (most of them situated between 42nd and 60th Streets), with the magazine footing the bill. The Tenement Museum does not cover such expenses for its employees, in case you were wondering. Long, taking over the column from a fellow who called himself “Top Hat,” chose to be known as “Lipstick.” Since her identity was hidden behind the page, she often had a bit of fun with her readers, describing herself as a plump middle-aged woman, or a distinguished gentleman. Long was a broad with a great sense of humor and adventure – perfect for 1920’s Manhattan.

Her nights were filled with jazz, gin, and jitterbugging, and all of it made it into her column, which became extremely popular. According to historian Joshua Zeitz, author of Flapper: Madcap Story of Sex, Style, Celebrity, and the Women Who Made America Modern, Long’s exploits often found their way to the office: “She would come into the office at four in the morning, usually inebriated, still in an evening dress and she would, having forgotten the key to her cubicle, she would normally prop herself up on a chair and try to, you know, in stocking feet, jump over the cubicle usually in a dress that was too immodest for Harold Ross’ [the founder of the New Yorker] liking. She was in every sense of the word, both in public and private, the embodiment of the 1920s flapper.”

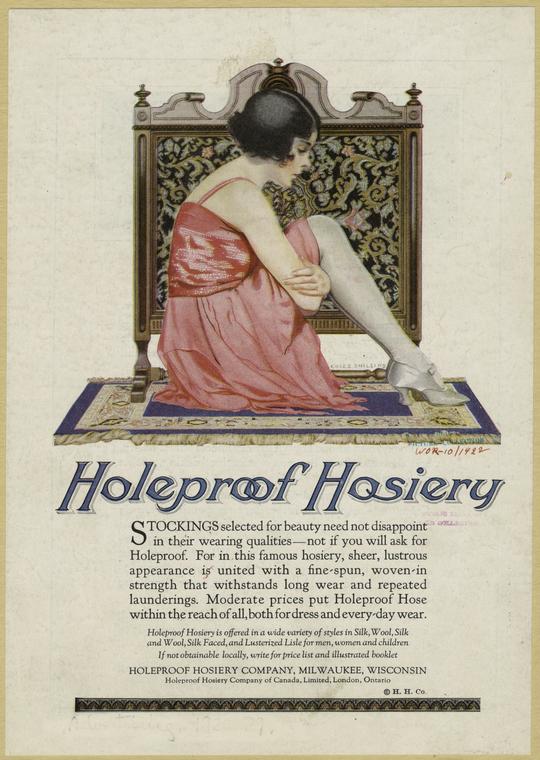

"In olden days a glimpse of stocking would have been looked on as something shocking" but by the 1920s long was flashing some leg on the beat and at the office. Advertisement courtesy of the NYPL.

There were an estimated 5,000 speakeasies in Manhattan during Prohibition (and another 10,000 in Brooklyn), and “Tables for Two” was a running series on how New York City flagrantly disobeyed the Volstead Act, or the law that prohibited the creation or consumption of alcohol. And while certainly not all New Yorkers spent their nights in speakeasies (because of the limited supply of quality liquor, working men and women often couldn’t afford to go out, much less drink at home) Long recounts the drinking culture of the Jazz Age in ebullient and often amusing anecdotes, like this one, from an early “Tables” that describes a raid on a speakeasy:

“It wasn’t one of those refined, modern things, where gentlemen in evening dress arise suavely from ringside tables and depart, arm in arm, with head waiters no less correctly clad, towards the waiting patrol wagons. It was one of those movie affairs, where burly cops kick down the doors, and women fall fainting on the tables, and strong men crawl under them, and waiters shriek and start throwing bottles out of the windows.” For those who may be curious, Long avoided trouble after this incident, with the police officer allowing her an elegant egress via the fire escape.

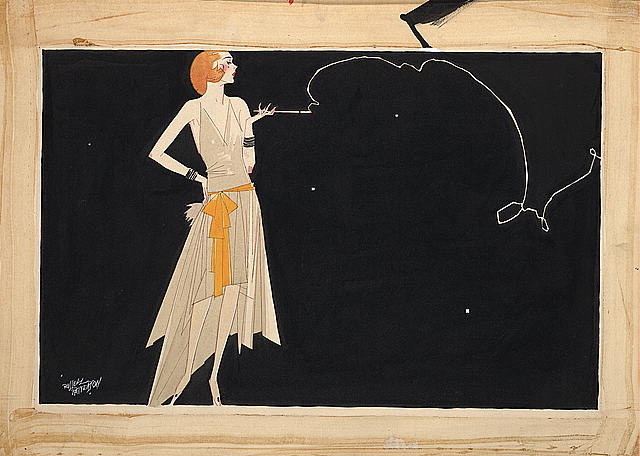

Everyone was so young! With looser clothing for women, came the loosening of social expectations. Lipstick was an apt avatar and recorder of these new free-spirited women. Image courtesy of the NYPL.

As the decadent decade of the 1920’s aged, Long matured. In 1927 she married New Yorker cartoonist Peter Arno, and the two had a daughter soon after. She continued to write “Tables for Two,” albeit more sporadically, as she focused most of her attention on her fashion column “On and Off the Avenue.” Not only did motherhood change Long’s all-nighters from booze bottle to baby bottle, but the Stock Market Crash of 1929 changed American culture away from a Devil-may-care attitude and towards a long-awaited drying out. The last few columns of “Tables” have a nostalgic tone – intoning how everything was once better than it is now:

“They have become so charming, these speakeasies de luxe, that there has been a trend among the bright young drinkers toward a glass of sherry before meals instead of cocktails, a bottle of wine during dinner, port with the cheese, a liqueur with the coffee — instead of one highball after another. If things continue to progress in this alarming way, we are going to have a nation of gourmets on our hands who never heard of drinking for the effect and not liking the taste. Apparently, satiation with a hard-liquor diet can accomplish the same temperance that light-wine-and-beer laws promise to.”

“Tables for Two” may have sobered up and settled the bill on June 7th, 1930, but the party continues every night in the City that Never Sleeps. So next time you go out for cocktails, say cheers for “Lipstick,” the friend who always knew the best parties.

Interested in seeing the Tenement Museum after dark? Contact Evening Events Manager Alana Rosen at [email protected] for more information on our public and private evening programs.

— Posted by Lib Tietjen, Evening Events Associate