Blog Archive

Joys and Sorrows: Lewis Hine at Ellis Island

All photos courtesy of the New York Public Library

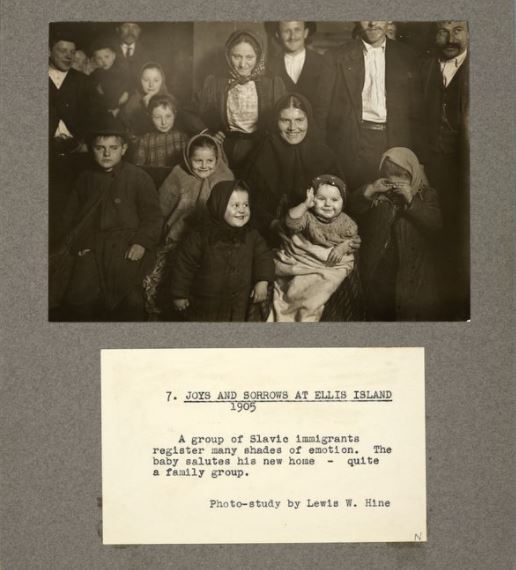

Lewis Hine was a social photographer, whose work literally changed the world. His most famous work captured, with great risk to his own safety, the invisible child laborers who worked difficult and dangerous jobs at the turn of the century. The newness of the photography medium combined with Hine’s beautiful and haunting portraits of working children led to fundamental changes in child labor laws in the United States.

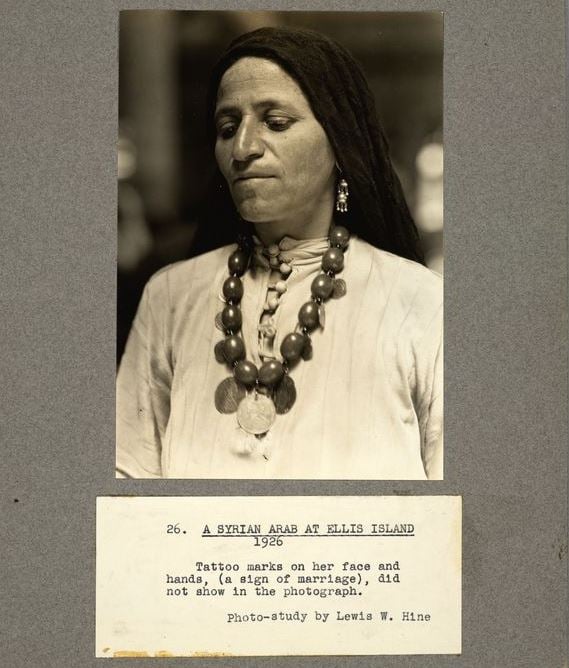

But a few years before he began his work for the National Child Labor Committee, he worked at the Ethical Culture School in New York City as a teacher and school photographer. His first assignment was to photograph contemporary immigrants arriving at Ellis Island. Some of these photos are available to view in the New York Public Library’s digital collections. Many of these photos were taken between 1905 to 1909, but Hine also returned to Ellis Island in 1926 to take pictures, after immigration quotas were implemented.

As he did later with his child laborer photos, Hine made sure to photograph his subjects with respect and dignity. Because of the limitations on photography equipment at this time, candid pictures in this collection are few and far between. Hine’s photos are more like modeled portraits, his subjects posed but no less authentic and honest. Not to mention, getting permission from these immigrants would have been exceptionally difficult, considering both the many language barriers between Hine and his subjects, as well as the magnitude of people passing through Ellis Island at the time (about 5,000 immigrants per day at its peak).

Not unlike today, popular opinion of immigrants at the time wasn’t the most flattering. Hine’s work didn’t set out to reproduce the same old stereotypes of the day, nor create a spectacle of the “foreign” or “exotic.” He wanted to show immigrants as everyday people, just like “you and me,” trying to work hard and provide a better life for their families. His hope was for people to look upon his photos and feel, as Hine himself said, “the same regard for contemporary immigrants as they have for Pilgrims who landed at Plymouth Rock.”

His photos emphasize the relatability of his subjects, whether they’re front-facing portraits or grouped family photos, whether they’re dealing with the tireless bureaucratic processes or the unending wait. Like the Tenement Museum, Hine sought to humanize immigrants, to make their journeys, their wants, their struggles indistinguishable from any American.

His photos emphasize the relatability of his subjects, whether they’re front-facing portraits or grouped family photos, whether they’re dealing with the tireless bureaucratic processes or the unending wait. Like the Tenement Museum, Hine sought to humanize immigrants, to make their journeys, their wants, their struggles indistinguishable from any American.

Hine would later go on to photograph the living and working conditions of immigrants, but his Ellis Island work serves to preserve a specific moment, and capture the spirit of migration. Everyone photographed had already endured an arduous journey to arrive at Ellis Island, but their odyssey was far from finished. Hine was able to focus on those complicated and human feelings of anxiety and hope, exhaustion and anticipation, as these men, women, and children stood at the way station between their old world and a new one.

- Post by Gemma Solomons, Marketing & Communications Coordinator at the Lower East Side Tenement Museum