Blog Archive

In Northern Ireland, a Resiliant Jewish Community

The history of Northern Ireland is infamously complex but no one can dispute the importance of religion in the region. Which is why it’s all the more fascinating that Belfast welcomed a Jewish community that remains to this day.

Why Belfast? Jews began arriving in Belfast in the 1860s and 1870s drawn to Belfast and Ulster at large by the linen and wool trade. Mostly arriving from Germany, the Jewish families were perhaps already involved in the business of exporting textiles across Europe.

Among some of the family names of Jewish settlers in Belfast are some which might look familiar to German-Jewish residents of the U.S.: Jaffe, Loewenthal, Boas, Betzeold and Portheim. The region was the site of the largest linen thread company in the British Isles: Coulson’s Linen Factory which was in operation from 1766 till the 1960s. The area was also home to a Barbour garment factory, an old name is British cloth goods, now perhaps more synonymous with the luxury market which is their current market. The German-Jews were perhaps already merchants in Germany, encouraged into this trade by longstanding regulations against Jewish land-ownership. Religious ceremonies have been held in Belfast since 1860 and the first synagogue was built in 1871 on Great Victoria Street.

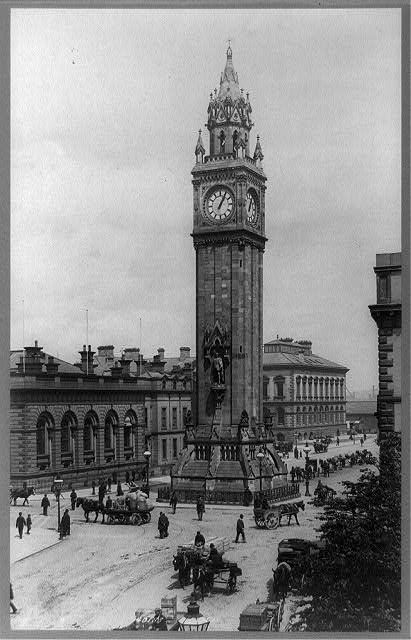

The Jewish population were successful merchants and some soon rose to prominence within the community. Daniel Joseph Jaffe is commemorated still by a drinking fountain in the Victoria shopping center. His son, Sir Otto Jaffe, was elected ‘Lord Mayor’ of Belfast twice. One of the most prominent ship yards in Ireland – the Harland and Wolff Shipyard world famous for producing the Titanic – was owned by Gustav Wolff whose family was German-Jewish but converted before he was born.

The Titanic when it was still a dream, under construction at the Harland and Wolff shipyard. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.

The German-Jewish population did not maintain a seamless presence in Belfast. It was not religion but nationality which drove some of this population out of Belfast as rampant anti-German sentiment settled over the British Isles during WWI. The Jews were not always free of discrimination. When Jewish children hoping to play tennis were refused membership in a local country club in 1926, the community rallied to build their own community center.

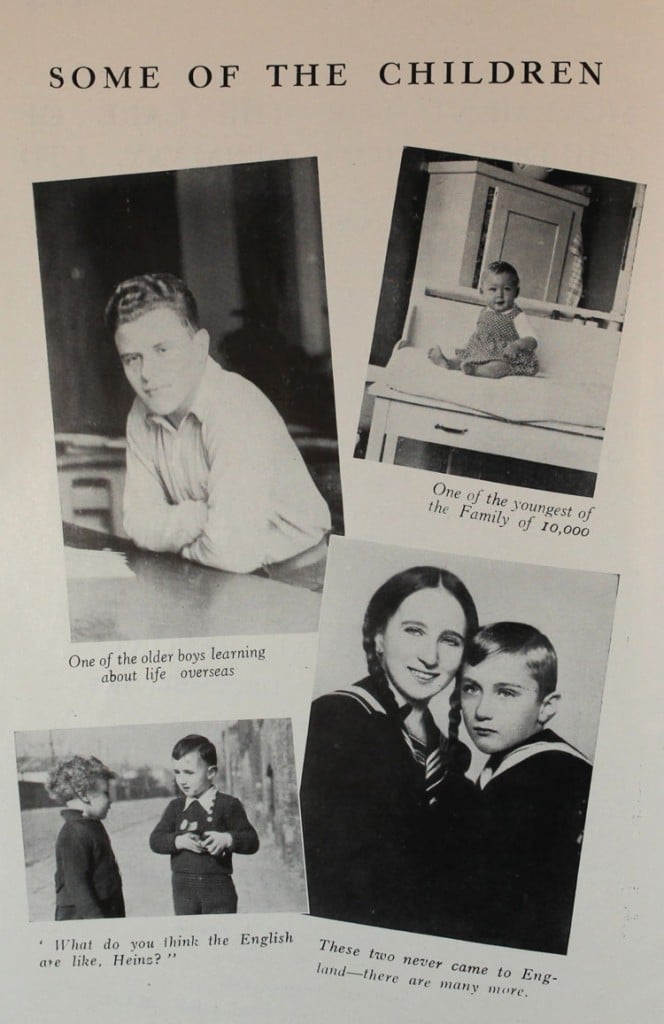

However, Eastern European Jews fleeing religious persecution is Lithuania and Poland also found a home in Belfast. Belfast was also one of the cities which welcomed children escaping Nazis slaughter on the eve of WWII through operation kindertransport.

A somewhat promotional pamphlet from the National Archives of the United Kingdom showing some of the children saved by kindertransport and encouraging families to welcome more. Photo courtesy of the National Archives of the United Kingdom.

Jewish professionals drifted away from Belfast after the war looking for opportunities abroad. When some of the windows of the Belfast Synagogue were smashed by vandals in 2014, the Belfast community – from many faiths – came together to condemn the attack.

The community today hosts interfaith events and continues be active in philanthropic causes and festivals which reach the region’s residents of all faiths. Blossoming after the long violence of the Troubles, Belfast itself is seeing something of a renaissance. Who knows what unexpected populations the city may attract today?