Blog Archive

Getting “Hooked” – 19th Century Human Smuggling on the Mexican Border

Next week’s Tenement Talk discusses After They Closed the Gates, an exploration of Jewish illegal immigration to the United States from 1921 to 1965. Many of the Jewish migrants who illegally entered the country during that time used human smugglers to aid their journey into the country.

Contemporary human smuggling is perhaps more prevalent than ever; people are smuggled either into or out of nearly every country in the world. Immigrants use smugglers to help them escape natural disaster or political unrest, or to simply try to make a better life for their families in a new country. Closest to home, human smugglers known as coyotajes (“coyotes”) help Central American and Mexican immigrants sneak across the U.S.-Mexican border. Smugglers like this have been bringing people over the border for over 120 years.

In the late 19th century, the United States passed severe immigration restrictions which established quotas of immigrants allowed from each country. Two notable laws of the era were the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which outlawed Chinese immigration, and the Immigration Act of 1885, which banned contract labor from outside the United States. These laws, which were intended to curb immigration and create jobs for native born Americans, in effect created a massive labor shortage across the country, most severely in the South and Southwest – a shortage that Hispanic immigrants could easily fill.

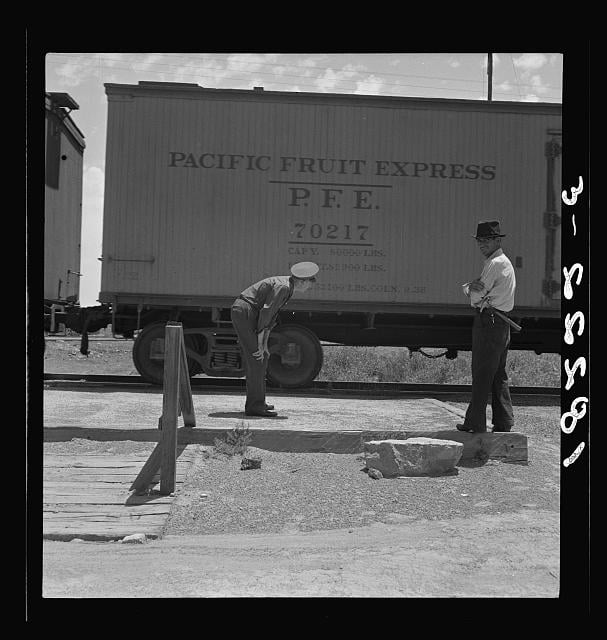

U.S. officials check a train for smuggled Mexican immigrants. Photo courtesy the Library of Congress.

Because of the labor shortage, American companies hired Mexican smugglers to bring immigrant laborers into the United States. These smugglers, called enganchadores (literally translated to “hooker” from the noun “hook” and the verb “to hook”), were labor recruiters who convinced Mexican peasants to make the trip north into the United States on the newly completed Mexican-American railways, guaranteeing jobs once in the U.S. According to David Spencer’s book Clandestine Crossings: Migrants and Coyotes on the Texas-Mexico Border, the enganchadores would accompany the migrant laborer on the train, ensuring their delivery to the American company that requested them.

Despite the fact that the border was not well guarded, the enganchadores were still breaking U.S. law. An 1891 law “prohibited the importation of alien laborers by the use of advertisements circulated in foreign countries which promised employment.” The methods used by the enganchadores was often not legal either – they “convinced” men by getting them drunk or conspiring with Mexican authorities to coerce vagrants and criminals, shipping them off to America without their consent.

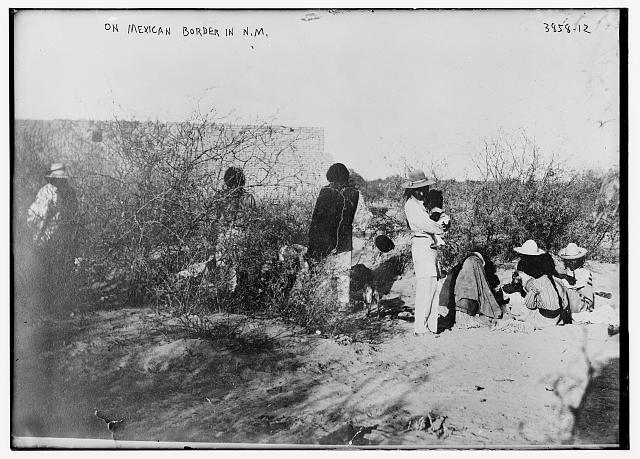

The U.S.-Mexican border in New Mexico, between 1915 and 1920. Image courtesy the Library of Congress.

Once laborers were “hooked” and in the United States, the jobs that the enganchadores had promised them were often much worse than what had been originally offered; much of the time, the enganchadores would not have the migrant worker sign a contract until they were already in the U.S. Some migrants were treated no better than chattel and were held until they could repay their transportation debts – a form of indentured servitude.

It is estimated that enganchadores smuggled thousands of men into the U.S. from the 1880’s to the 1910’s, and most of them worked for American companies in the Southwest.

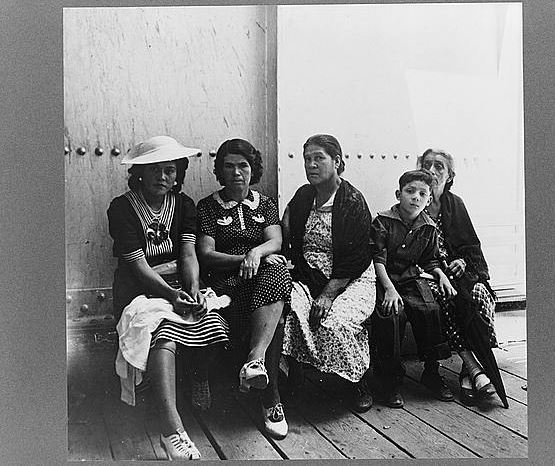

Mexican immigrants wait at an Immigration Station in El Paso, TX, 1938. Image courtesy the Library of Congress.

Contemporary coyotajes act much like enganchadores in that they are middlemen between Mexico and the United States for hopeful immigrants. While coyotaje are not recuiters for specific American companies like the enganchadores were, their existence is a continuation of the enganchadores’s legacy.

The Tenement Talk, After They Closed the Gates, is at 103 Orchard Street on Monday, April 21st at 6:30 PM. For more information on this free event, click here.

– Posted by Lib Tietjen