Blog Archive, Great Reads

Gettin’ Schooled: A History Lesson

August 30, 2016

Grammar school class photo of Sam Jaffe. Sam Jaffe was born in 97 Orchard Street in 1891. He went on to become nominated for an Academy Award in 1951. Back of the photo reads “about 1909”. “Picture courtesy the collection of Nicholas Dembling.”

The current school system in place in the United States is relatively new, not even a hundred years old. It’s hard to believe that the push for free access to education for all children was met with controversy and dissent. But the right to an education was hard fought over many years throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries.

The use of child labor during the Industrial Revolution is a black mark on one of the most important time periods in Western history, and the development of Child Labor Laws and Compulsory Education Laws were a synchronized movement to combat this problem over a period of several decades. Before then, children were either taught at private institutions for those who could afford it, by religious organizations, or instructed at home.

But many children — such as those living on 97 Orchard Street during this time period — would often be working long days, every day to help provide for their family’s food and home, some of them working in factories for 70 hours a week. Factory work was not like the farming work children have done with their families since hunter-gatherer times that continues to this day; instead kids were working in difficult, dangerous, and dirty conditions with very little compensation. They didn’t have much time for resting, let alone going to school or having fun the way kids should.

Glass factory, working at midnight. Lewis Hines. Photo from the New York Public Library

Compulsory education laws were seen as a way to try and curb the abuse of child labor. These laws state that every child, with some exceptions like homeschooled children, must attend a public or private institution for a specific period of time. The first was enacted in Massachusetts in 1852 and the last in Mississippi in 1917, and they were seen as a way to prevent factory owners from exploiting children, since their school attendance was mandatory.

It took a long time for these state laws to be instituted on a national scale. New York State passed Compulsory Education laws in 1874 and again in 1894, but without funding for fighting truancy, it was difficult to enforce.

Following the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire in 1911, the New York State Legislature created the Factory Investigating Commission to study and proposes changes to working conditions. After discovering the horrible environment families and children – some as young as five – were laboring under, they proposed a change to state laws that “prohibit[ed] children under fourteen from being employed at factory work in any location, including tenement houses.” These changes were challenged and deemed unconstitutional, and it wasn’t until 1941 that the Fair Standards Labor Act of 1938 fixed the minimum age requirements for children at no younger than 14 for some jobs. This national policy was in part a way to cure the child labor ill but it also served to open up the job market to adults during the Great Depression.

Coinciding with the Industrial Revolution was a major influx of immigrants entering the country and inhabiting large urban areas during this time period. The number is estimated to be close to 20 million between 1880 and 1920. Many native-born Americans were concerned with the growing diversifying population, and access to American schools became a great way for immigrant children or the now native-born children of immigrants to become assimilated into American culture.

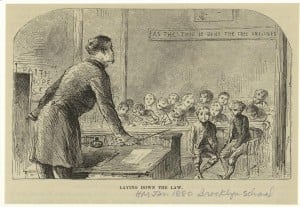

“Laying Down The Law.” 1880. Photo from the New York Public Library.

One of the things these foreign children were taught in this time period was how to read and speak English, and an appreciation for American history, government, and rhetoric — as well as other subject matters not unfamiliar to children today, such as basic arithmetic and literacy skills. Textbooks from the 19th century show just how similar school subjects were to today, although the classroom setting was very different from how we’re educated these days. A single classroom often had kids of various ages and education levels, with the older students helping teach the younger ones in what’s known as the Lancasterian model. Teachers were mostly young, unwed, pious women who administered much harsher disciplines for unruly students.

Of course, if one has any questions about what life was like for an immigrant child attending American schools at the height of the immigrant influx into the country, they could always Meet Victoria Confino and ask her all about it.

- Post by Gemma Solomons, Marketing & Communications Coordinator at the Lower East Side Tenement Museum