Blog Archive

As Time Goes By: 1935 on the Lower East Side

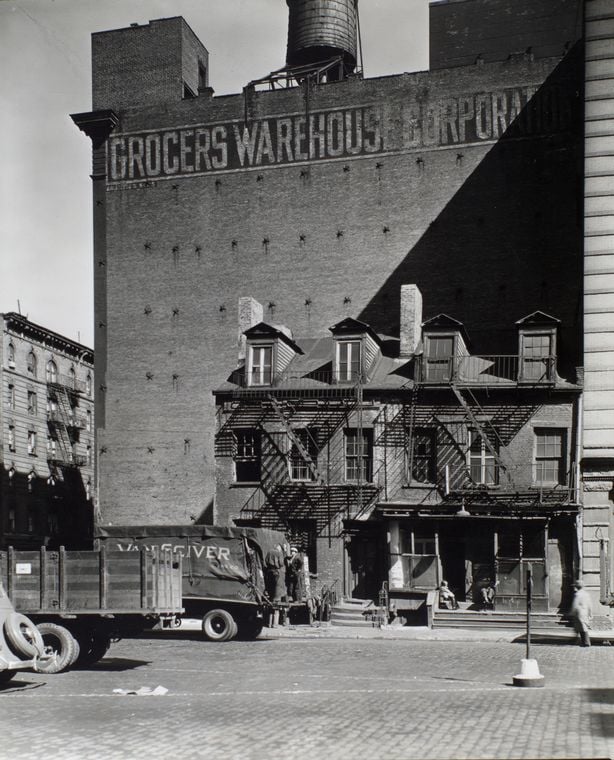

The evolution of New York Streets is thrown into stark relief in this image from 1935 taken by Berenice Abbott as part of the Federal Art Project. Courtesy of the NYPL.

In many ways, the year 1935 was the end of an era for a tenement building at 97 Orchard Street on New York City’s Lower East Side. After almost a century of acting as a threshold to the New World, the building was condemned when the landlord was unwilling or unable to incur the costs of mandatory structural updates. This is not to say that the building was completely empty; as recently as the 1980’s there were various storefronts that continued to operate on the ground floor. This story was repeated all over the Lower East Side, keeping the neighborhood in business: literally. The communities who once lived in the neighborhood continued to run businesses and shop the area maintaining a vibrant immigrant hub. As a community of immigrants, Lower East Side has been especially impacted by global events, and though 1935 saw the shuttering of 97 Orchard Street, it also saw enormous changes across the country and around the world.

Although the world was on the brink of a second world war, some of the news from 1935 still seems innocent from the vantage of 2016. It was in 1935 that airplanes were banned from flying over the White House. Franklin Delano Roosevelt banned airplanes, based not on the security concerns but because they were interrupting his sleep. It seems almost as naïve to think that Presidents are entitled to sleep as that airplanes were a danger only to a good night’s rest. Today it seems that the ban did indeed buttress national security. President Roosevelt had a lot on his mind with the Great Depression and in 1935 devised a perhaps the most brilliant remedy of his presidency: the Works Project Administration (WPA).

Designed to provide employment and income to Americans who had lost their jobs and businesses in the economic collapse, the Works Project Administration would eventually employ 8.5 million Americans supplying an average salary of $41.57 a month. (One of those recipients was Adolfo Baldizzi, a former resident of 97 Orchard Street). Harry Hopkins, a man of “modest means,” was the director of the administration. Perfectly embodying the project’s philosophy, he once noted: “Give a man the dole and you save his body and destroy his spirit. Give him a job and you save both his body and his spirit.” In the hostile environment of the Dust Bowl, this teach-a-man-to-fish philosophy was the answer to a national need.

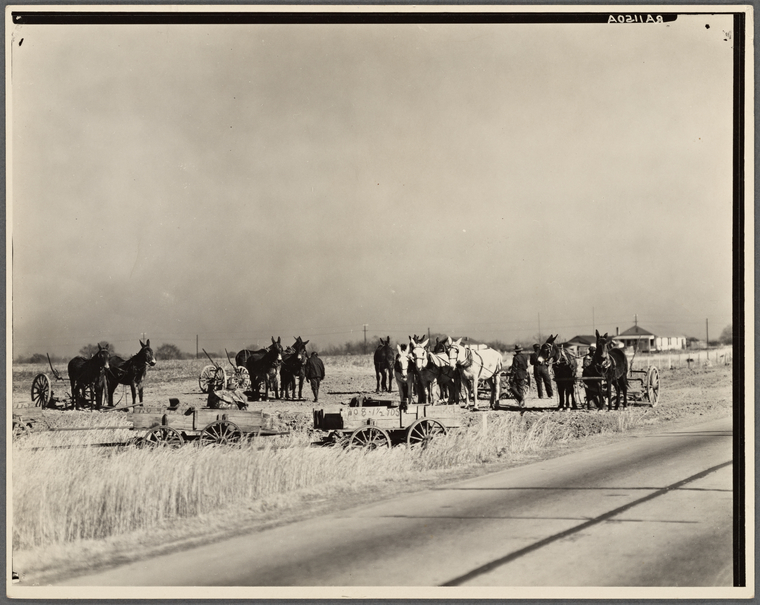

Men work with mule teams outside of Montgomery, Alabama. Much of American farmland was devastated by the drought. This image was taken as part of the Works Project Administration. Photo courtesy of the NYPL.

We often speak at the Tenement Museum about the difficulties of industrial occupations. But the Lower East Side was not unaffected by the devastation of U.S. agriculture during the thirties, which reached its peak in 1935. While not responsible for the Great Depression, it sure did make matters worse. The Dust Bowl was the name given to the disastrous drought which ravaged the land and the farms of the Midwest. The disaster got its name in 1935, when Robert Geiger of the Associated Press used the unforgettable phrase, “Three little words achingly familiar on the western farmer’s tongue, rule life in the dust bowl of the continent – if it rains” . The drought affecting the Midwest was only made worse by treacherous dust storms which choked the air with the dust of a parched landscape. Devastated farmers moved west hoping for help and work, but often found more scarcity. This tragic migration was in turn made infamous by John Steinbeck’s classic novel, The Grapes of Wrath.

While 1935 had its challenges domestically, the situation was sinister abroad. In Germany, a nation suffering from its own economic crisis, 1935 also saw the passing of the Nuremberg Laws which institutionalized some of the most toxic Nazi ideology. The laws excluded Jews from German citizenship, government positions, and from receiving degrees as doctors and professors. The laws ignored ‘religious’ grounds for Jewish faith, using genealogy rather than faith to determine who was Jewish. All Germans with three or four Jewish grandparents were affected. While making life hostile at home, the Nuremburg Laws also made emigration difficult for Jews, levying taxes which stripped Jews of property and savings as they left the country.

In 1935, some Jews were hoping to find refuge in British controlled Palestine. The previous year saw record Jewish immigration to the region, but as a harbinger of gathering tension, the British government moved to limit Jewish immigration to appease Palestinian residents. Some Jewish Germans were able to join the extant Jewish community of the Lower East Side, though they in turn would struggle in the privation of the Great Depression.

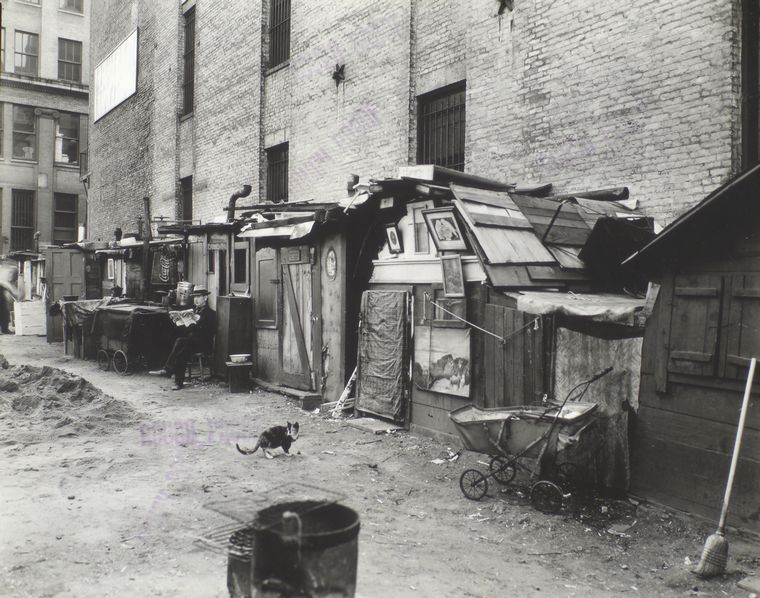

A settlement of the unemployed on Houston Street. Photo also by Berenice Abbott in 1935. Image courtesy of the NYPL.

It goes without saying that the story of immigration on the LES didn’t end with the shuttering of 97 Orchard Street. The “Golden Door” remained open to immigrants on the eve of World War II and changing immigration policy was about to alter the landscape of this already diverse neighborhood.

—Posted by Julia Berick, Marketing and Communications Coordinator