Blog Archive

Whose Project?

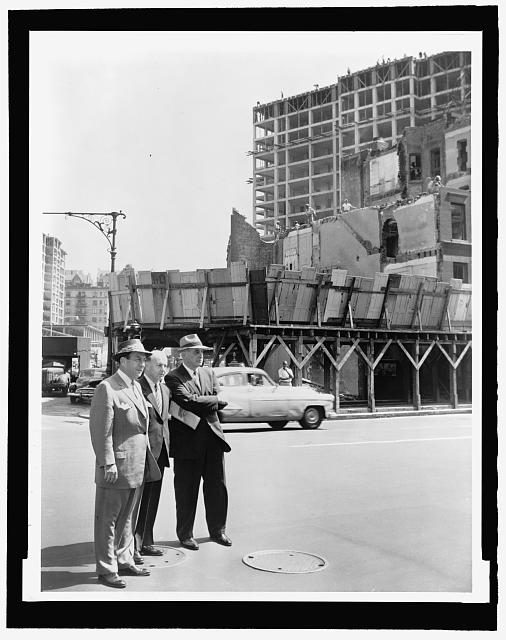

Influential, postwar urban planner Robert Moses, right, tours a future public housing site on August 9th 1956 with Mayor Robert Wagner, left and Frank Meistrell, center. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.

I live in a housing project. Recently a blogger blasted my project’s landlord for trying to pass off the project as luxury housing. Apparently a housing project is a low-class place to live, no matter how hard you try to make it attractive to young professionals through landscaping and amenities.

But let’s turn back the clock. What did America think about the housing project after World War II? As it turns out, the housing project wasn’t always synonymous with crime and poverty. Indeed, for a few years midcentury the housing project provided stiff competition to the bedroom suburb with its detached, single-family homes and white picket fences.

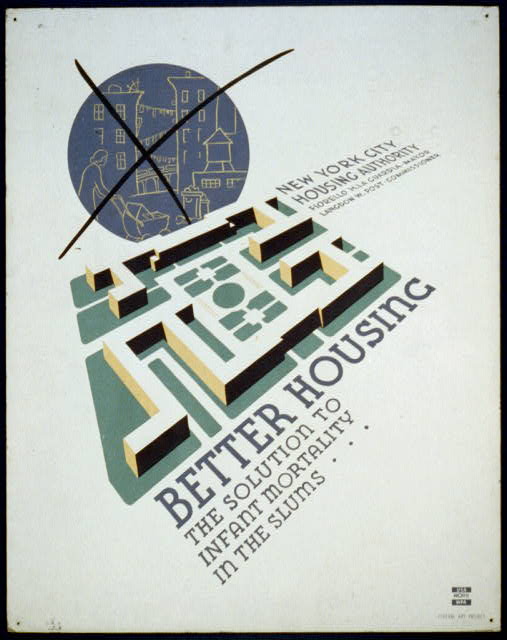

This poster from 1938 created by the New York Housing Authority offers housing projects as as hygienic solution to infant mortality. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Imagine you’re a returning war veteran in 1946. You grew up in an aging tenement sharing space with your siblings, struggling to earn enough to one day support a family. You return from combat and into a colossal housing crisis. Even after you land a good, steady job, you wonder how you’ll ever afford a better place to live.

But this being the 1940s, you know who to turn to for help: the government! After all, it was the government that steered the country through the Great Depression and a world war. Surely the government can also solve the housing crisis.

And that’s what the government did. First, it encouraged suburbanization by insuring mortgages and investing in highways. But it also encouraged urban renewal by loaning cities money to clear-cut tenement neighborhoods for housing projects.

This 1941 photo illustrates the beginning of decades of slum demolition, making way for housing projects. This photograph courtesy of the LOC.

A housing project isn’t necessarily a home for the poor. It isn’t even necessarily government-owned. A housing project is nothing more than a group of apartment buildings (and occasional townhouses) designed, constructed, owned, and managed as one unit, with the buildings and the surrounding land creating a (hopefully) harmonious whole. A typical housing project includes playgrounds, walkways, greensward, parking lots, and access roads. Residents easily flow from one space to another. Garbage collection and sewers are designed for maximum cleanliness and efficiency. Buildings are typically T-, L-, X-, or Y-shaped to that every apartment is a corner unit with optimal air circulation. In a housing project all the problems of the tenement district – all the mess and grunge and danger of urban living – would be expelled by design, and residents would finally reach their full potential as Americans and as human beings.

Although some housing projects were built for the poor, most were built for other classes. Lincoln Towers, the housing project behind Lincoln Center, is a luxury housing project. And although the government often owned the low-income housing projects, middle- and upper-income projects were privately owned. My housing project is Stuyvesant Town, built in 1947 by the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company.

A view from 1951 of the fountain and other landscaping details in Peter Stuyvesant Village, the author's housing project. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.

In no city was the housing project as widely embraced as in New York. Hundreds of thousands of New Yorkers of all classes and in all five boroughs still live in these projects, most of them built in the quarter-century after World War II.

When they were new, these housing projects represented a better, modern future. But by the 1970s the projects had fallen into ill repute. To find out why, take a walk down Grand Street on the Lower East Side.

As you head toward the East River, you’ll find yourself sandwiched between two very different housing projects. On your right, the Grand Street Co-op, a middle-income, owner-occupied housing project built in 1957 by labor unions as a way to provide improved and affordable housing for unionized blue-collar workers and civil servants. On your left lies Seward Park Extension, a low-income, city-owned housing project begun in 1973 and never finished. Why didn’t the City finish building Seward Park Extension? Look again to your right.

For most of its existence, Seward Park Co-op has been predominantly white and Jewish. But by 1973 the poorest New Yorkers were predominantly African-American and Puerto Rican. The residents of Seward Park Co-op did not want the crime and social disorder of the urban poor across the street from their middle-class project. African-American and Puerto Rican New Yorkers, however, were no longer willing to live in the shockingly decrepit, overcrowded tenements, and they resented what they perceived as the Jewish community’s attempt to “close the door behind them” as they moved out of poverty and into the middle class. As the two sides battled each other in court, in the press, and in City Hall, construction of the rest of Seward Park Extension stalled. Eventually the City abandoned all plans to finish this low-income housing project, leaving much of the land a vacant lot for 45 years.

This image of a housing project in Red Hook Brooklyn is a more bleak version of 'hygienic' planned housing. This photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Racial and class divisions shaped the suburbs, too, but the government’s role in suburban development was indirect. Developers didn’t need much government help buying and clearing cheap farmland for suburban development. Independent realtors, not a centralized Housing Authority or corporate landlord, handled home sales. Banks, developers, and realtors could create all-white suburbs with little oversight or opposition.

In the city, by contrast, everything was out in the open and highly politicized. The long-standing racial- and class-based residential segregation, much of it illegal, is much easier to address when the government builds housing projects, but does the government want to address this segregation? It’s an emotional and contentious issue, so it makes more sense to avoid it by pulling the plug on housing projects, which is exactly what government did in the 1970s. By the 1980s low-income housing projects were suffering from rising crime and crumbling infrastructure, while wealthier New Yorkers increasingly sought homes in the “reclaimed” tenements, lofts, and brownstones of gentrifying neighborhoods.

Today the housing project has an unsavory reputation, but not because of anything inherently unsavory about the housing project. It’s just another model for the urban built environment, and in my experience a great one to inhabit. The problem isn’t the housing project; it’s our own inability or refusal to solve the problems of racism and poverty in America.

– Posted by Adam Steinberg, Senior Education Associate