Blog Archive

The Power of the Purse

Something about the Lower East Side definitely brings out strong women, whether they be mothers, students, nurses, shopkeepers, rioters, laborers, activists, hagglers, or a bit of all of the above! Since March is Women’s History Month, we’re celebrating all women who have graced our neighborhood with their affection and audacity. Today we’re talking about the thousands of women who made an impact on the neighborhood where it really counted – the economy.

Nathalie Gumpertz, who lived in 97 Orchard Street in the 1880's, raised three daughters on her own (after her husband left for work one day and never came home) and made a living as a dressmaker.

In the early 20th century, most of society, including the scientific community, agreed that women were inherently weaker and less intelligent than men (in 1870, a retired Harvard Medical School professor wrote that women who went to college and spent significant time on rigorous study could impair their ability to conceive children). Prejudices against African American and immigrant women were even stronger.

At the same time, however, women were considered to be the moral and emotional center of the family – they were to have as many children as possible and raise them to be upstanding Americans. Because of the consensus that women were incapable of taking care of themselves or of higher thought, most working class women, like those who would live on the Lower East Side, often could not make their own choices about their education, living or working conditions, romantic partners, reproductive rights and medical treatments, and other vital aspects to their lives and had no say in national or local politics.

A 1914 Puck magazine cartoon highlighting the plight of women in the home. Anti-suffragists said that a woman was "The Queen of the Home," but as Puck says, she was nothing more than a slave to the stove. Image via the Library of Congress.

The one thing that many working-class ladies of the Lower East Side could control, however, was the family finances. According to historian Gail Collins, in her best-selling and riveting book America’s Women, husbands of all ethnic backgrounds gave their wives full control of their paychecks, saving just enough for lunch, taxi fare and entertainment. Even men who had controlled finances in their home countries gave up their paychecks to their wives in America. Not only did women manage their husbands’ (and daughters’) finances, but they also managed the money that boarders brought in! In 1900, over half the households in 97 Orchard had at least one non-family member living in the apartment, and the wife acted as a mini-landlord to the boarders.

Controlling the cash flow was a great responsibility for women, as they had to be vigilant for every cent: “The wife saved up and paid the rent, bought the food, and allocated money for other expenses,” as well as learn to budget. Monthly rent was something completely alien to many immigrants, who had come from farm life in Europe, and putting a little money aside every week for rent was often difficult. “When money ran short,” writes Collins, “the wife had to placate creditors, scrounge money from friends and relatives, or talk storeowners [sic] into allowing her to run up a tab.”

Despite their lack of rights, many immigrant women controlled the family finances. This included making a budget and doing the shopping for food, as these women are doing on Hester Street in 1898.

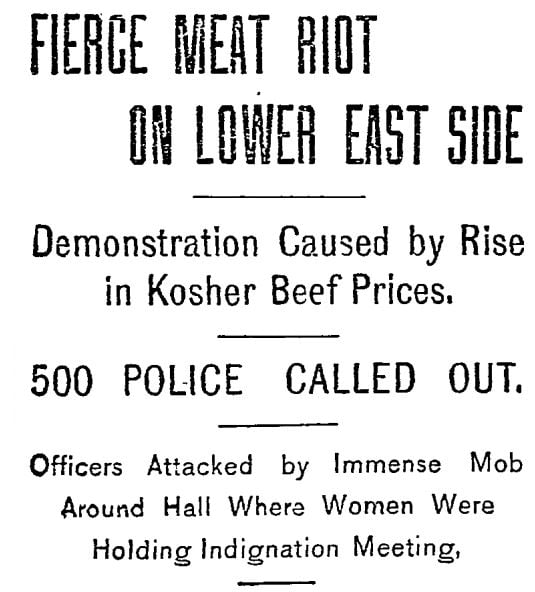

Women also had a hand in controlling how those store owners set their prices. Women had the very potent power to boycott a store out of business, or even worse, to directly attack the store, like the Kosher Meat Boycott of 1902 that happened right here at 97 Orchard Street! Women, furious over the rising price of Kosher meat, took the streets in protest, throwing meat and bricks through butcher shop windows. The Kosher Meat Boycott, which took place over 3 weeks in May, succeeded in lowering the price of meat in the neighborhood. The boycotts even extended to the Bronx and Brooklyn, with women all across the city assaulting shopkeepers, customers, and police. Despite what science, and often their husbands said, these women dared to be heard!

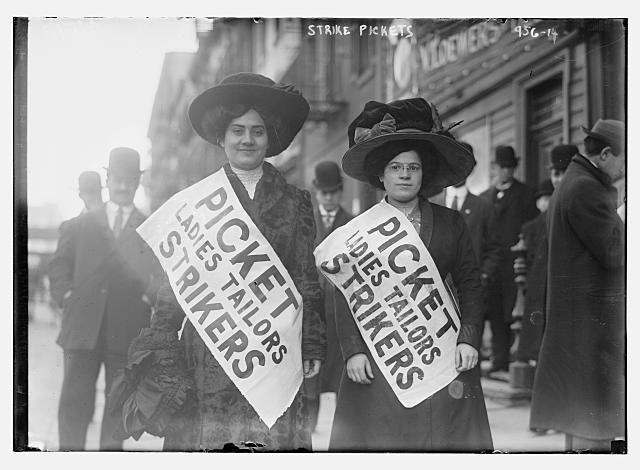

This “power of the purse” extended to the workplace as well. Young immigrant women made up the vast majority of all textile workers in the early 1900’s, and when they came together to fight, they threatened the multi-million dollar industry enough to get them to concede. In November of 1909, 20,000 workers, most of them young Yiddish-speaking women, went on an 11 week strike of the garment industry; the largest strike in American history. Called the Uprising of 20,000, the strike centered around low wages and long hours, dangerous workplace conditions (that often resulted in fires, like the famous Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire in 1911), and what we would today call sexual harassment. The companies hired prostitutes and local gangsters to abuse the strikers, both physically and verbally, and the police and courts were largely unsympathetic.

Two striking workers pose for the camera during the Uprising of 20,000. It's hard to know whether the men behind them were there to support or to harass them. Photo taken February 5th, 1910, towards the end of the strike. Image via the Library of Congress,

After 11 weeks of strikes and legal battles, the Uprising of 20,000 ended, not a complete victory, but with some concrete accomplishments. According to the Jewish Women’s Encyclopedia, “Out of the Associated Waist and Dress Manufacturers’ 353 firms, 339 signed contracts granting most demands: a fifty-two-hour week, at least four holidays with pay per year, no discrimination against union loyalists, provision of tools and materials without fee, equal division of work during slack seasons, and negotiation of wages with employees. By the end of the strike, 85 percent of all shirtwaist makers in New York had joined the ILGWU” (International Ladies Garment Worker’s Union).

This month, we remember not only the women whose names have gone down in history, but the thousands of women who made it without any intention of doing so – they were just trying to make new lives here in America.

– Posted by Lib Tietjen