Blog Archive

Singing the Unsung: Ben Shahn and Labor in United States

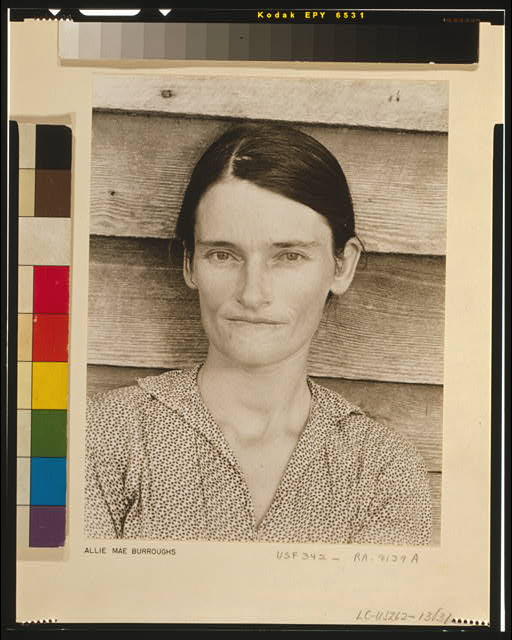

One of many lingering images by Walker Evans for the Farm Securities Administration. This image is of Allie Mae Burroughs an Alabama sharecropper, taken in 1935 or 1936. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.

The Farm Securities Administration isn’t exactly the place you would think to look for art. In 1935, when the Farm Securities Administration was created to provide support for the rural poor, the Administration set out to prove that there was poverty that required immediate ministration. No problem there. In much the same way some Government agencies use auditors and statistics, the FSA deployed artists and photographers to document both the work of the Administration and the continuing need for its existence. Though the subject was bleak- or perhaps because it was – some of America’s finest artists, Jacob Lawrence, Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans and Ben Shahn did some of their best work for the FSA. In the field, rather than lose faith in the U.S. laborer and the farm, many of these artists developed a new respect for those who had been stricken by disasters both economic and natural. Though some of these artists were born and raised in the United States, growing up with the lore of America’s strength and endurance, Ben Shahn was actually born in Kaunus, Lithuania. He became one of thousands of his generation who learned to love his new homeland with an articulation almost rivaling his American-born peers.

Shahn emigrated from Lithuania with his family in 1906. As for many immigrants growing up in the first half of the 20th century, work shared a premium with school. Luckily for Shahn, work was also art. Shahn apprenticed for a lithographer while in high school, working during the day and attending school at night. Eventually, Shahn would attend NYU and the National Academy of Design from 1917 to 1921. But it was at the Farm Securities Administration where Ben Shahn did some of his most seminal work. Inspired by Walker Evans, Shahn took photographs of farms across the United States. Unlike Evans, Shahn also created paintings based on these photographs.

The American farmer wasn’t Shahn’s only political focal point . His early work focused on one of the conditions he knew best: the isolation of the city dweller.

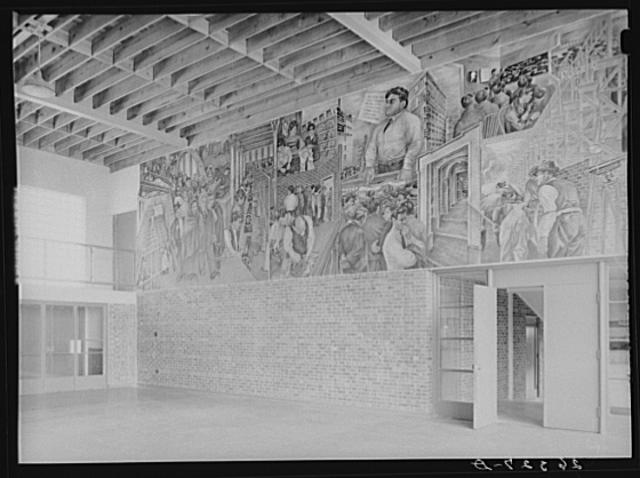

A Ben Shahn Mural in the Wilbur J. Cohen Federal Building in Washington, D.C. Built in 1940, the Cohen Building continues to remind us of a time of socialist art in government buildings.

Shahn also devoted himself to defending and beatifying less beloved versions of the U.S. laborer. Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti were Italian immigrants who were known to be politically radical. When a series of murders broke out in the Boston Metropolitan Area, allegedly committed by Italian radicals, Sacco and Vanzetti were arrested. With little evidence against them, Sacco and Vanzetti were convicted of murder and put to death. Shahn’s 23 works, specifically on the plight of Sacco and Vanzetti, allowed him to venerate by association hundreds of immigrants and labor advocates whose opinion and background was seen as threatening or anti-American.

It was a thin line for many, between celebrating the American worker and touting controversial socialist polemic. Even in celebrating American workers, Shahn edged a little too close to controversy. One of Shahn’s most famous works was a mural for the Bronx Central Annex Post Office, an egg tempera on wet plaster, a fresco, of the “Resources of America.” The work depicts the nobility of the American worker in steel mills and in fields as well as the proudest industrial developments of the day: hydroelectric dams and factories.

Part of the fresco, and part of the inspiration for the work, is a quote from Walt Whitman’s “As I Walk These Broad Majestic Days.” The fresco originally boasted a quote also from Whitman which was deemed, however, too controversial for a United States Post office. The original quotation was from Whitman’s “Thou Mother with Thy Equal Brood”. Many objected to the lines:

“To recast poems, churches, art, (Recast, maybe discard them, end them – maybe their work is done, who knows?)”

A Jesuit Professor at Fordham formally denounced the mural for this challenging content. Shahn, who had seen the works of Diego Rivera destroyed in Manhattan for similarly controversial content, agreed to change the mural’s text to something more palatable. (Shahn had worked with Rivera on his mural for Rockefeller in Detroit and had met his wife there, with whom he worked on the Post Office mural.) Once the public was satisfied with the message of the mural, Shahn’s work should have been safe in the American canon. When Shahn died in 1969, he had had his work on the cover of Time Magazine numerous times, not bad for a little boy from Lithuania.

However, the mural has a few more adventures before it. In October 2012, the Bronx Central Post Office lobby, with its works by Shahn, was officially named a Landmark. The Post Office has since sold the building to a private developer, Youngwoo & Associates, who purchased the Building for an undisclosed sum. This has been the fate of many post offices around the country. Though around 1,100 contain public murals like Shahn’s, not all of this artwork has been protected from destruction. At the timepublic works for Post offices, like art for the Farm Securities Administration was a boon to working artists during the depression.

30 Rockefeller Center without the benefit of Diego Rivera's communist manifesto. (This imagine is actually of the Post Office in Rockefeller Center which was not the intended location for Rivera's work. ) Photo courtesy of the NYPL.

So where might we see the next surge of profound American art? Post offices may not be the answer, but can we look to the Government to inspire another generation of American art? As we wait for the next chapter in public works, we can be grateful that even during the darkest years of the Great Depression, government programs brought together relief, remarkable artwork, and another proud immigrant happy to depict his adopted home.

–Posted by Julia Berick, Marketing and Communication Coordinator