Blog Archive

On This Day: 1863, The New York City Draft Riots

On this day in 1863, Lower East Side residents would have been very uneasy. The smoke and noises in the streets would have just begun to recede. 150 years ago today brought an end to what had become the biggest and deadliest civil insurrection in American history – the New York City Draft Riots. While much of the violence and destruction happened away from what is today the Lower East Side, the ramifications of the events certainly would have been felt here.

Spanning three days, July 13th through the 16th, 1863, the riots were the culmination of the longstanding working class – and largely Irish – racial, political and religious resentment of the government. Working-class Irish immigrants had suffered inflation, food shortages, and virulent discrimination and unemployment; but the match that touched off the powder keg was a set of new Draft Laws which took effect on July 11th. The Draft Laws stated that stated that all single men (including immigrants who had filed for citizenship) between the ages of twenty and forty-five and all married men between twenty and thirty-five could be called upon to fight the ongoing Civil War on behalf of the Union Army. Another statute of the Act stated that if a man could afford to pay $300, he could hire a substitute to be drafted in the wealthy man’s place.

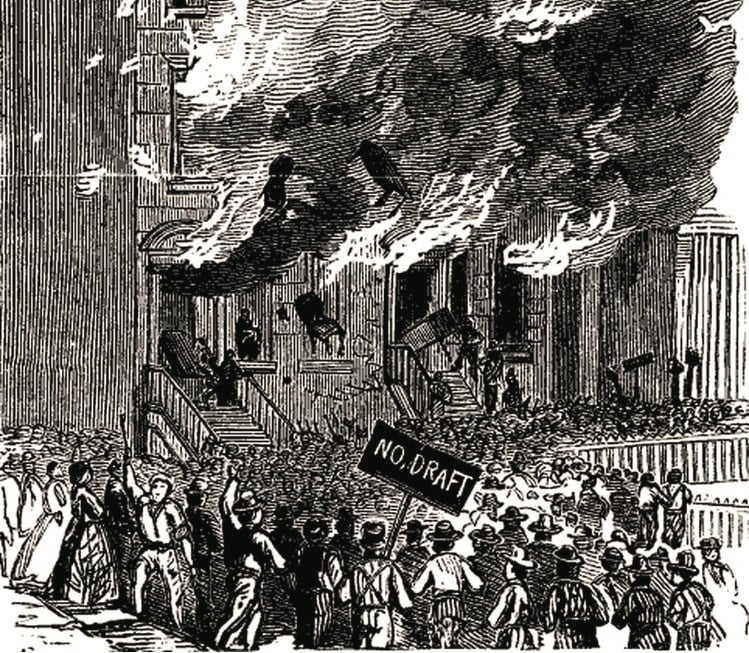

At approximately 6 a.m. on the sweltering morning of July 13th, a group of hundreds of men walked the streets carrying signs and banging metal pans to protest the draft. The group, swelling in number, made their way to the provost marshal (head of military police)’s office on Third Avenue, where the draft lottery was scheduled to occur at 10:30 am. A group of voluntary fire departments, mostly made of Irish immigrants, became enraged at the loss of so many of their men to the draft that they burned the draft office and beat the Police Superintendent, John Kennedy, nearly to death.

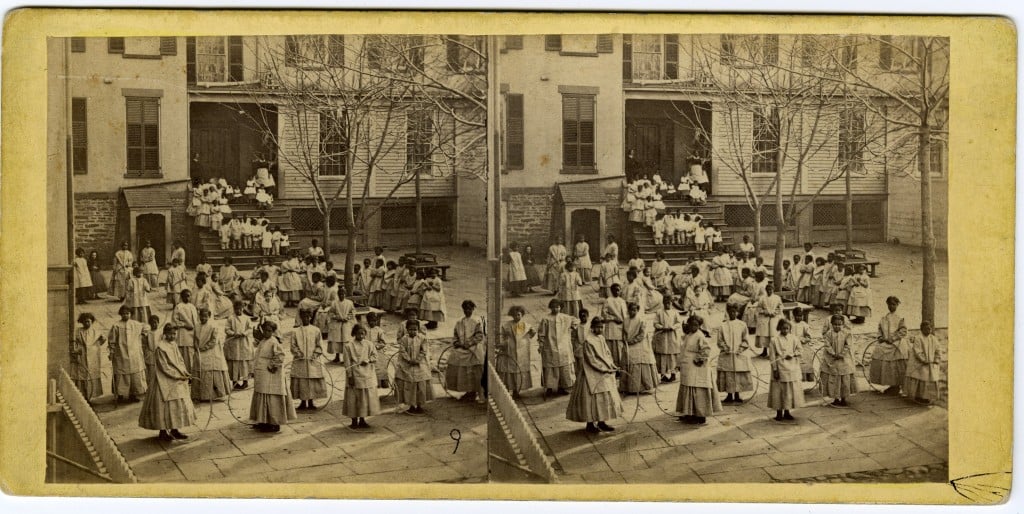

By the afternoon, and over the next two days, New York was engulfed in violence. The mob set fire to the homes of well-known Republicans and wealthy families’ mansions on Fifth Avenue; Irish Catholic members of the mob targeted Protestant churches and charities; protesters even burned the city’s arsenal. A significant portion of the violence was racially motivated towards African Americans, whom the mob believed were the impetus for the Civil War. The Colored Orphan’s Asylum on West 44th Street was set afire, but thankfully all 237 children inside escaped safely. At least eleven African American men were murdered during the three day riot, and fear of continued violence ultimately contributed to a 20% decrease in the African American population of New York City during the Civil War.

The Girls Playground at the Colored Orphans Asylum, burned on July 13th, 1863 - Undated photo courtesy of The Jeffrey Kraus Collection

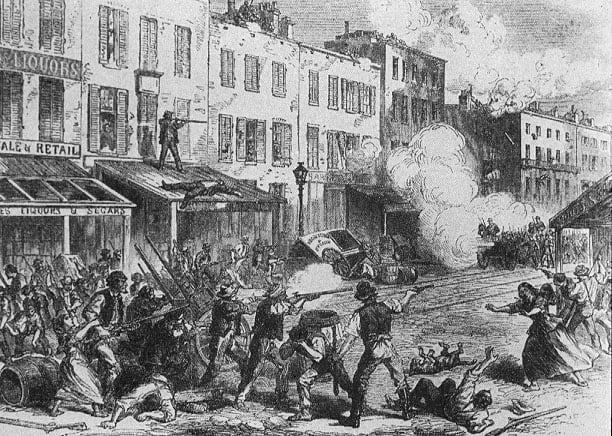

In Lower Manhattan, where both The New York Times and The New York Tribune were headquartered, the mob turned their violence toward both publications. Henry Raymond, owner and editor of The Times, personally manned a Gatling gun to keep the protesters at bay. The rioters attacked the headquarters of The Tribune, whose editor, Horace Greely, was well known for his anti-Irish editorials.

Federal troops, fresh from the battle of Gettysburg, arrived in New York City on Wednesday, July 15th and fierce fighting ensued until the next evening. By Friday, 6,000 troops were stationed in the City and the riot had been suppressed. In the aftermath, the draft continued at a lesser rate than originally planned. 67 rioters were convicted of their crimes, but none received long sentences.

While the Draft Riots and their racial overtones are certainly a painful chapter in the history of the Lower East Side, they also serve to illustrate the systematic disenfranchisement that both the African American and the Irish communities were facing at the time. 1863 was the year that the tenement at 97 Orchard was built and the year that future 97 Orchard resident, Bridget Meehan, later Bridget Moore, immigrated to the United States. It is almost certain that she knew of the riots, and maybe even witnessed some of the violence or its after effects.

The Draft Riots of 1863 should serve to remind us that while New York City can sometimes be oppressive -even violent. We’re working toward a better future by learning from even the uncomfortable memories of our past.

– Posted by Lib Tietjen