Blog Archive

Immigration and Independence

Photo courtesy of the New York Public Library Digital Collections.

For many first generation immigrants, there is a difficult and delicate balance between keeping the connections to their homeland as strong and vibrant as though they’d never left, and finding new understandings and identity in their adopted country. The divide in loyalties is strong on an average day, but especially so on Independence Day – the most patriotic day in an already patriotic country.

While Independence Day has always had its own connotation for Americans, it has had a different significance for immigrants. Throughout the decades, it has historically been used as an opportunity to further Americanize immigrants, both within their own communities as well as with outside pressure from “native-born” citizens.

In the past, it was a day when many immigrants felt the need to affirm their American identities. In 1889, German Jews on East Broadway formed an association known as the Educational Alliance, which provided, among other things, English language training to European Jews. The organization naturally saw the Fourth of July as a great time to educate new citizens on American customs and traditions. The Fourth of July Encyclopedia describes one such holiday celebration in 1906 where hundreds of immigrant children and 800 parents gathered to celebrate their new homeland, although the reception to these poor kids sounded mixed at best:

“The Declaration of Independence was read in Yiddish and English…. Everybody, immigrants and natives, shouted as the youngsters, with hands outstretched towards the colors said with solemnity ‘we salute thee.’ After that the children sang ‘Our Own United States’ and three young lads, having limited English training, attempted to read Daniel Webster’s speech at Bunker Hill. The affair ended with a rough rendition of ‘America’. According to one reporter, ‘Although the words had been printed for them on their programmes, they were in English, and they floundered badly in the tune.’”

And if you’re curious how a patriotic American song sounds in Yiddish, here’s a 1916 example from the King’s Orchestra in New York, “America, ich lieb’ dich” – or “America, I love you.”

Naturalization ceremonies on the Fourth of July became widely popular as mass citizenship oaths began early in the twentieth century. They were the result of the increasing influx of immigrants to the United States and the unfavorable political conditions that led them to emigrate in the first place. According to The Fourth of July Encyclopedia, it also came about as awareness increased of “the important contributions immigrants make to the fabric of the nation.” In 1921, the League of Foreign-born Citizens” established a program of consecration on Independence Day for new citizens” with the hopes Americans would feel a sense of “warmth and friendliness” towards immigrants.

In 1915, the Fourth of July briefly went from Independence Day to Americanization Day, as an attempt to bridge the divide between American-born citizens and naturalized immigrants. The Immigrants in America Review sent out a call to all citizens, born in and outside of the U.S., “to get together as one nation and one people for America, in peace or war.” The Review believed that a diverse population was beneficial for the country, but “if American ideals and purposes and opportunities are to be fully realized, the barriers that separate the newly naturalized citizen from the native born must be swept aside.”

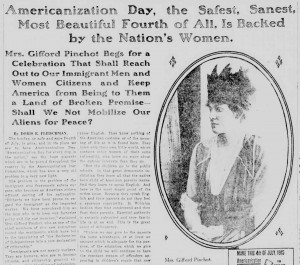

Newspaper clipping courtesy of the Library of Congress.

The New York Tribune, dated June 7, 1915 encouraged the “Nation’s Women” in particular to reach out to immigrants and “Keep America from Being to Them a Land of Broken Promise.” Mrs. Gifford Pinchot – born Cornelia Bryce, a noted Suffragette and Labor Reformer in the day – begged societal women to celebrate Americanization Day in particular for the sake of immigrant women, whose husbands are out in American society working and whose children are being assimilated in American schools. “Immigrant women have been utterly neglected by this government,” Mrs. Pinchot said back in 1915. “…Most of them do not know that they are in America, with all the connotation which that name carries to the native of this country. Or they weakly realize that they are disappointed in what they have found here.”

She pointed out that while it was difficult in bigger cities like New York or Chicago for immigrant women tending house day to day to avoid American influences, immigrant women in rural neighborhoods could go their entire lives without hearing a word spoken in another language, and were basically living back in their home towns. Mrs. Pinchot’s hope that Americanization Day would “inspire in them an American patriotism and make America in reality the melting pot which it is so fondly called.”

Independence days, at their center, are celebrations of liberty. Over the centuries, the move for many immigrants into the United States has often been an exercise in freedom – actively hunting down what they felt eluded them in their own homelands, be it religious, political, or economic. And then there are those who came into this country through no decision of their own – displaced or stolen peoples to which freedom must seem an abstract and far away concept. Whether you yourself are an immigrant or the child of immigrants, whether you are rejoicing over a 1776 revolution or rejoicing over a day off work, embrace the cultural identity to which you ascribe. Be all-American. Be half-American, half-elsewhere. Be all-elsewhere. You are free.

Photo courtesy of the New York Public Library Digital Collections.

- Post by Gemma Solomons, Marketing & Communications Coordinator at the Lower East Side Tenement Museum