Blog Archive

Hyphenated And Good: Filipino American Heritage Month

In 1915, Theodore Roosevelt said, “There is no such thing as a hyphenated American who is a good American.” One hundred and one years later, here I am: a child of immigrants from the Philippines, born and raised in the United States, and writing this in October during Filipino American Heritage Month.

In 1915, Theodore Roosevelt said, “There is no such thing as a hyphenated American who is a good American.” One hundred and one years later, here I am: a child of immigrants from the Philippines, born and raised in the United States, and writing this in October during Filipino American Heritage Month.

So much can shift and change in the span of a century.

During the time Roosevelt made this statement, the United States was on the brink of World War I against Germany. Subsequently, many aspects of German America were then perceived as suspicious and threatening, including German-Americans themselves. It was also a time when the Philippines was officially a U.S. colony. This was after Spain had rooted its kingdom in the soil of the country for over three hundred years. Spain lost the Spanish-American War in 1898, and for a brief moment the Philippines was independent. Then came American occupation for nearly fifty years.

The ideas of Philippine sovereignty finally became a reality in July of 1946. In the aftermath, what remained for the Republic of the Philippines would be a complicated and multi-layered political, economic, and financial tie with the United States. English was the second official language, and the dream was America.

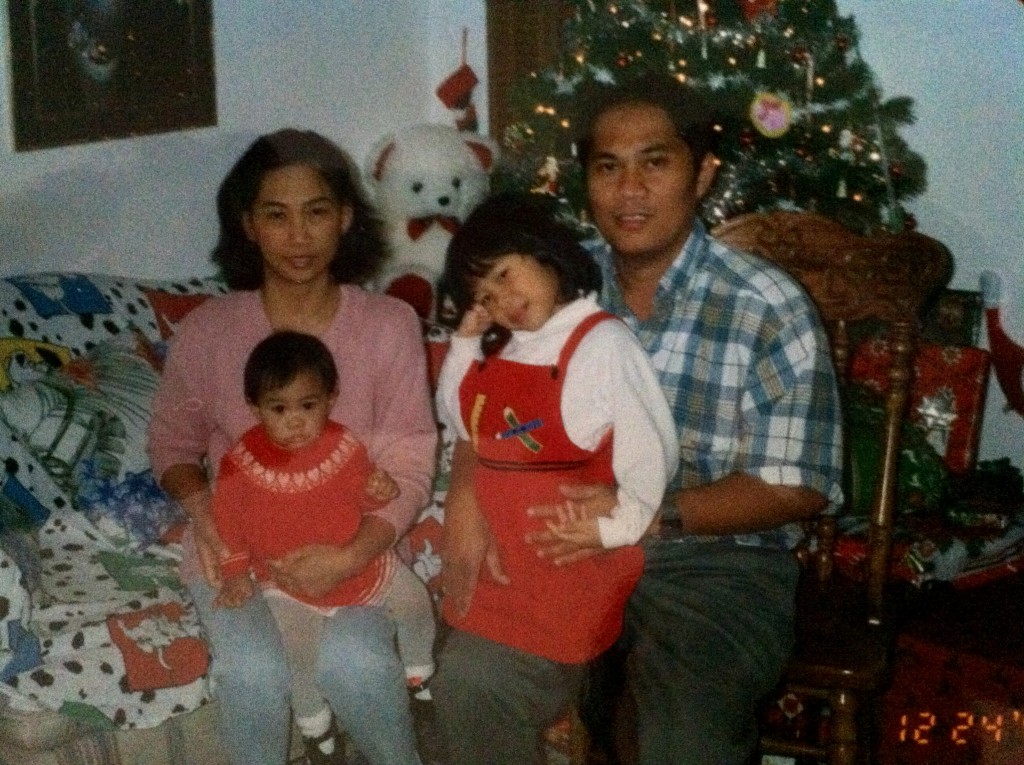

Like many immigrants before her, my mom, a registered nurse, would seek out this dream for herself when she arrived in 1986. What she left behind was her family and her husband, whom she had only recently married. What kept her close but still a world away was her determination to get her family out of poverty. My father waited for her return and would reunite with mom for a few months at a time; eventually, after my first birthday in the States, she brought me back to meet him in the spring of 1990. At that point, dad’s immigration papers were still in process so mom was essentially raising me on her own in a small apartment in New Jersey. Shortly before she returned to America, my parents made the decision to leave me behind in Manila with dad and our extended family. My mom could not afford to keep me on her own and my dad did not want to see me go. She called me “the bridge that kept them together”. Even now, after all these years, there is still a hint of pain and regret in her voice when she speaks about this. In December of 1992, shortly after my sister was born, my dad and I permanently joined them in Philadelphia, just in time for Christmas.

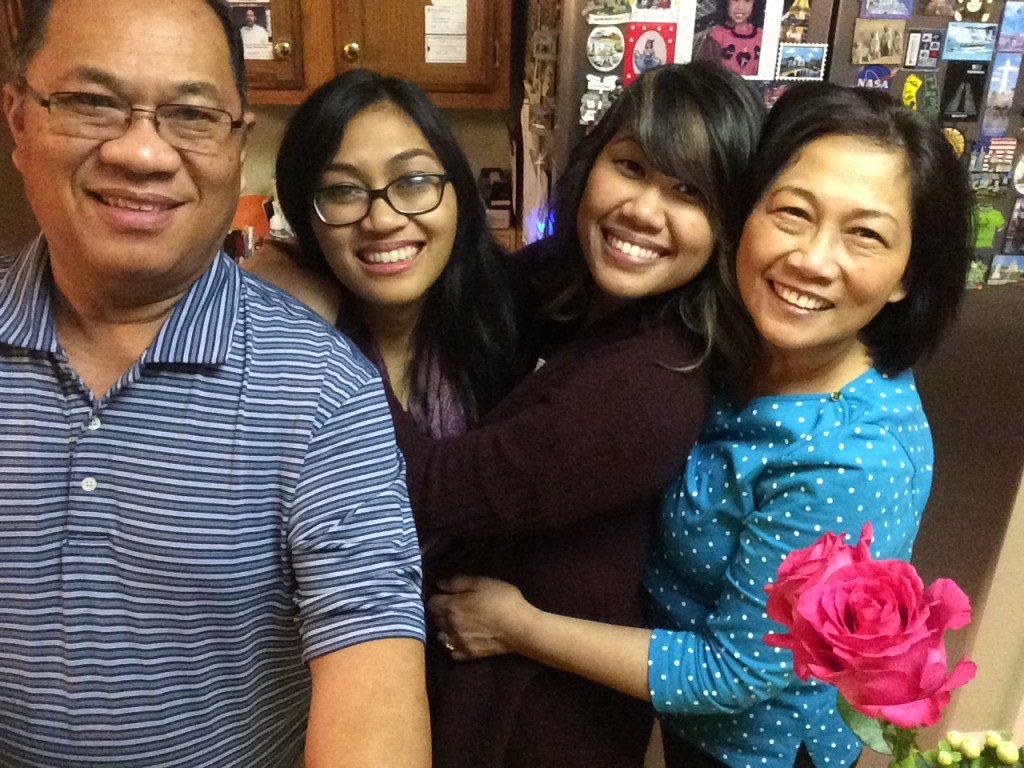

Since then, I think of the “American” experiences my family and I have had, including: moving to the suburbs of southern New Jersey, my parents becoming citizens, making Thanksgiving dinner with American and Filipino food on one table, and my sister and me graduating from college with honors. All the while, my parents were raising us in a country they themselves only came to know as adults. I feel like my mother’s Filipino daughter at her kitchen table, but when my sister and I speak effortlessly in English to our parents, it is America that falls off the tip of our tongues. It is “mommy” and not “nanay.” It is “The Star-Spangled Banner” we grew up singing and not “Lupang Hinirang.” It is Thomas Paine we learned about in school before Jose Rizal, the national hero of the Philippines, entered our consciousness. I imagine these were the moments my mom and dad realized they raised American children and felt at once a wonder and pride about us and a growing distance from my sister and me.

On the other hand, during a recent trip home, I saw all of our diplomas together for the first time. Along with our birth certificates, their marriage contract, immigration papers, and naturalization certificates, their college degrees from the Philippines are stored away with their children’s markers of progress. “If they ask, tell them we are educated,” said my mom.

Through any hardship my parents faced together, they are comforted by the saying: “Makaraos rin tayo.” Translated, it means, “We can recover.” I like to think it has become our family saying. Through the years, my Filipino immigrant family has faced the heaviness of distance, the ache of memory, the unimaginable pain of my mom and dad saying goodbye to their parents, siblings, relatives, and friends, and the sting of being seen as foreigners because of our brown skin and their accents. Their resilience is why I am Filipino-American.

A century later, I am among many that live what Roosevelt dismissed. It is more than possible to be a hyphenated American and good. As a child of immigrants, I have lived the dream of my parents into a reality. As an adult, I have fiercely embraced a significant part of my identity that for a time was lost to the pressure of assimilating into one idea of an American. At times, the balancing act is challenging. There are days when I feel my identities align, and then there are the moments when it splits me into two worlds and between two nations. In that struggle, I have found solace in the experiences of those historically and in the present who do not fully belong to one country or the other.

In my search for an America of Filipinos, I realize that those before me set down roots in this country that would pave the way for mom to do the same. The history of the Philippines is a story of resisting and surviving over four hundred years of colonization and like the United States, would call for revolution and demand freedom from not only Spain, but Britain’s former colony itself. In this truth, Philippine America is an American story. Filipinos have made the sacrifices like many groups in this country, developed the land, cooked the food, fought the wars, cared for the patients, taught the students, and raised their children to never forget where they came from and to remember why they are here. I celebrate a past where the hyphenated Americans struggled, celebrated, reshaped, and transformed the United States. I continue to live the present where this legacy is carried on today.

- Marianne De Padua is a part-time Educator at the Lower East Side Tenement Museum