Blog Archive

A Monument to Impermanence: The Death and Life of New York’s Penn Station

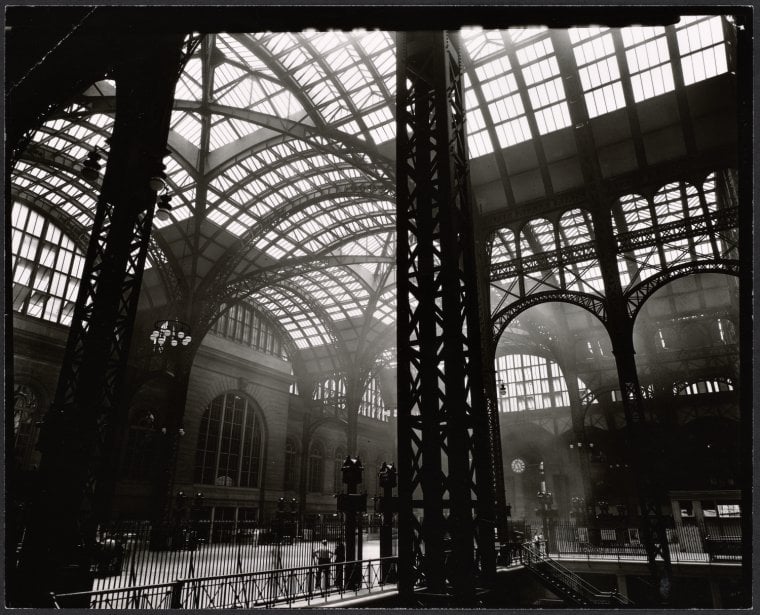

The graceful balustrades and soaring ceiling of the original Penn Station, designed by the architecture firm, McKim, Mead & White. Image courtesy of the NYPL.

It was lavish, grand, spectacular. It was marble and granite built in the classical style but it wasn’t a hotel and it wasn’t a mansion. It was a train station and everyone was welcome. Every generation gets the Pennsylvania Station it deserves. The original grand NeoClassical Penn Station was torn down in 1961 to make way for Madison Square Garden with commuter and train platforms in its bowels.

So far the jury is out as to which station this generation will receive. The debate currently swirls as to what, if any changes will be made to the current Penn Station, the much bemoaned addendum to Madison Square Garden Stadium a venue for music and sporting events and more.

Pennsylvania Station, mostly referred to as just Penn Station, is not in Pennsylvania. New York’s Penn Station is at 34th Street between 7th and 8th Avenues roughly. Roughly: because, as anyone who has tried to catch a train there knows, the labyrinthine corridors slither off far from the orginal site. The Penn in the name refers not really to Pennsylvania so much as to the Pennsylvania Railroad company, once the leading railroad company in the United States. Penn station, though it now serves all manner of confusing semi-governmental entities as Amtrak and the New Jersey Path commuter train was the sole creation of the Pennsylvania Railroad Company. Original station was an amazing feat of almost hubristic proportions and somewhat noble, populist undertones.

Another image of the interior of the original Penn Station taken in 1935 by Berenice Abbott. Photo courtesy of the NYPL.

Penn President, Alexander Cassett had just returned from Europe in 1901. Among other grand European monuments, he had seen the impressive Gare d’Orsay in Paris and had, accordingly, been impressed. At the Gare d’Orsay, stunning metal constructed balustrades and beaux-arts style benefited from extensive tunnels through which ran electric trains. Electric trains as much as any flourish struck Cassett. It was the electricity which was missing from his own plans for a station. He needed a means of connecting the Island of Manhattan with the main arteries of his extensive network. At the time many trains still ran on coal and there was a constant danger of asphifixiation when the trains passed through tunnels. Electric trains would make possible the tunnels under the Hudson and the East River for which Cassett had long hoped. Let me footnote the tragic trajectory of this blog by mentioned that the Gare d’Orsay, so impressive in 1901, is still impressive. The grand station encountered a moment of uncertainty in the midcentury. It is now safely and magnificently converted to the Musee d’ Orsay. You can visit any time.

After his hopes for collaboration with other railroad companies were crushed, Cassett realized Penn Railroads would have to shoulder the costs alone. The bill for the tunnels and station would run up to $100 million project. The Penn railroad company began building the station the way a behemoth in the early 20th century might, buying up property in New York’s tenderloin neighborhood. The area intended for the station was a poor one, and Penn sent 3rd party negotiators with wads of cash to buy low-income residents out of their homes. By the time the station was built construction had displaced hundreds of families. When thinking about the drawbacks of the current Penn Station, darkness and ugliness, primarily it is important to remember that the first station, though lovely came also at a cost. The further human cost of Penn Station came from the tunnels. Sandhogs as they were called were a markedly diverse group of laborers who together dug the tunnels under the Hudson. It was an epic undertaking and much has been written about the men who accomplished the task. When the crew tunneling from the Manhattan side met the crew tunneling from the Jersey side the tunnels were only misaligned by a fraction of an inch.

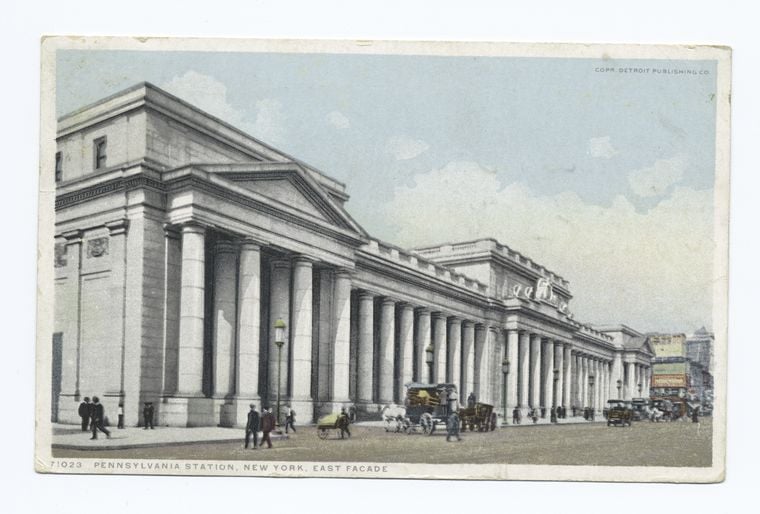

An image of the eastern facade of the original Penn Station. Courtesy of the NYPL.

The station when it opened was also a resounding success. After 4 years, 27,000 tons of steel, 500,000 cubic feet of granite, 83,000 square feet of skylights and 17 million bricks it was clearly a monument. Based on the public Roman baths of Caracalla, the architects McKim, Mead and White borrowed the majesty of a triumphant public place. The Station was meant to serve everyone and by all accounts it did. Visitors to the original station speak of the pride they felt at belonging in such a regal place. It felt like a gift from the gods and it was meant to last forever. But you know the saying, the lord giveth and the lord taketh away. Well…

How did Penn Station become a monument to impermanence? When was it too late for this impressive edifice? Read into it in Part II of our Penn Station history.

–Posted by Julia Berick, Marketing and Communications Coordinator